In their new book Healing Haunted Histories: A Settler Discipleship of Decolonization (Cascade Books, 2021), authors and life partners Elaine Enns and Ched Myers confront hard truths about settler complicity in historic and ongoing injustices perpetrated against Indigenous peoples. They also offer a way toward healing.

Through the lens of Enns’ own Mennonite family narrative, they examine the complex reality of how one traumatized people (Mennonites fleeing Ukraine in the early 20th century) unknowingly displaced other traumatized peoples (Indigenous peoples on the Saskatchewan Plains). Equal parts memoir, social-historical-theological analysis and practical workbook, Enns and Myers invite settler Christians (and other people of faith) into a discipleship of decolonization and restorative solidarity.

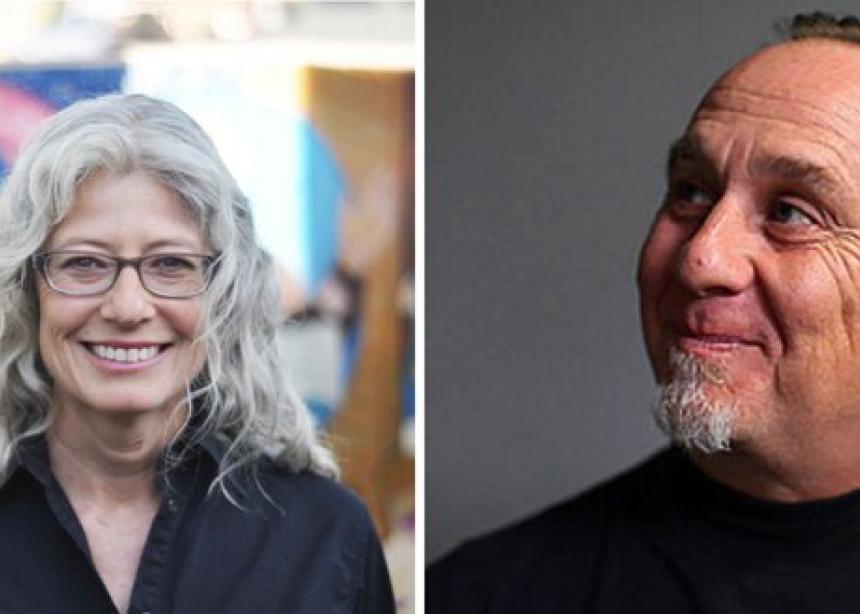

Elaine Enns has worked in a range of restorative justice fields since 1989. She has an DMin from St. Andrew’s College in Saskatoon, Sask., and trains and teaches across North America. Ched Myers is an activist theologian and New Testament expositor working with peace and justice issues. They are part of Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries and have strong connections to Nutana Park Mennonite Church in Saskatoon. They live in Ventura County, Calif.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What are your connections to Nutana Park Mennonite Church?

Enns: I owe my call into restorative justice work to the extended community of Nutana Park. In my research I worked with a lot of the older women in that congregation. They are brave and caring people.

Myers: We got married there in ’99 and I was received into the Mennonite Church there in 2008.

Enns: That’s where the babies in our family were dedicated. The funerals for my mom and dad were there. Most of my siblings were married in that congregation—it’s been a very important pillar in our life. The leadership there was also the first to marry a gay couple. They continue to do really good work.

Q: Elaine, what inspired you to write this book?

Enns: Growing up I knew that my grandparents had—all four of them—gone through a terrible time in Russia-Ukraine, but there was so much silence around it. At the age of 13, I interviewed my grandma and she described the beauty and abundance of Ukraine. But when she began to talk about her teenage years, she started to cry. She was generally a joyful person, so seeing her cry planted seeds of trepidation but also curiosity about what we carry as a Mennonite community. In my college years, I volunteered with the Big Sister Little Sister program. My little sister was a Cree girl. With her I began to understand how my ancestors were a part of displacing her ancestors. That experience drove me into the work of restorative justice. It led me to ask questions about our own Mennonite community, historically. How were they complicit, knowingly or unknowingly, in the dispossession and displacement of Indigenous neighbours?

Q: How would you describe this book to a church community, congregation or pastor?

Enns: I grew up with lots of stories of what it means to be Mennonite—stories about Ukraine. But what was missing from my family’s story— and for the most part from the Mennonite story— is the violence that we unwittingly participated in against Indigenous communities. Healing Haunted Histories is my exploration into those wounds, silences and hauntings, through the lens of a process we call Landlines, Bloodlines and Songlines. It is to help us, as settlers, find our way forward for the sake of our land, our societies, our faith, our communities.

Q: What exactly does “healing haunted histories” mean?

Enns: A couple of years ago we came across the work of sociologist Avery Gordon. From her book Ghostly Matters, I’ve understood that our soil is haunted. Individuals and communities are haunted by past and continuing violence on our land. In Canada, it’s the displacement and genocide of Indigenous people, in the U.S. it is that and also slavery. Gordon talks about how this haunting resides in us. These acts of the past and the continuing system of violence that we, as white settlers, participate in. She also talks about how we can heal from these hauntings, if we face them and work towards justice.

Myers: In our book, we use Jesus’ strange parable in Luke Chapter 9—when one demon is cast out from a person, seven more are ready to come in and take their place—as a kind of metaphorical framework for understanding how deep these hauntings are found in oneself, in our community and in our society. Take, for example, the recent trial in Minneapolis of the policeman that murdered George Floyd with his knee on his neck. Why was that such a big deal in the American consciousness? It’s a perfect example of a haunting. It’s not only white officers killing one Black man, which happens all too often. It taps into this unresolved legacy around race. In the U.S., this will keep re-cycling until we achieve justice. That’s why we decided to lead with that image of a haunting, because we think it’s an evocative one that speaks to our condition.

Enns: A few years ago I was walking in my old neighbourhood in Saskatoon and I saw some graffiti on a fence in an alley. It said, “As long as the sun shines, grass grows and the river flows,” which is from the text of the treaties made between the Canadian government and Indigenous peoples. Most of these Treaties have been violated or broken by settlers. This back alley scrawl is a haunting from our common history in Canada. It represents a covenant text that needs to be revisited and embraced but also a commissioning to us to heal and make things right.

Myers: In this insular suburban neighbourhood stands this challenge: right here, on Treaty 6 land, is this unresolved question of justice. We have the same things here locally, in Ventura County. The truth is, there is no corner of Turtle Island that has been untouched by this legacy and, hence, by these ghosts. That’s why this book—which takes a deep dive into the particularity of Elaine’s family system—is very much a workbook for any settler in North America, because the questions are all similar.

Q: Tell me about the structure of the book. What are Landlines, Bloodlines and Songlines?

Enns: These are three storylines in the book. “Landlines” explores where our settler ancestors came from, the push-and-pull factors of their immigration. In the second part of the book, it explores where they settled and then how we have settled and keep resettling. I have been migratory. I’ve moved many times, touching down on different land. Landlines is about exploring the stories of violence, displacement and struggles for justice on those lands. “Bloodlines” is the story we carry in our bones, our embodied story. It’s what we’ve inherited biologically and psychologically from our family, race, ethnic, gender and cultural formation. I think of it in terms of who we were taught to be in our community, how we inherit intergenerational trauma and how we inherit strength, courage and faith, too.

Myers: Our communal narratives tend not to tell the whole truth. They are often distortions or omissions that cast our communities (including families and denominations) in a heroic light but are silent on how we were complicit in the broader story of colonization.

Enns: “Songlines” are the convictions of our faith. They’re the pieces that give us courage and foster resilience. They help us to work for justice and the healing of ourselves, of self and society. In the Mennonite tradition, there are many Songlines. Refugee resettlement work was very important to my parents as was Mennonite Disaster Service. The work of Mennonite Central Committee and Mennonite Church Canada’s Indigenous Settler Relations are other Songlines.

Q: Can you explain what you mean by “discipleship of decolonization”?

Myers: We understand this as life work that is both personal and political. That’s why we refer to it as discipleship. It involves moving in an arc toward restorative solidarity and away from settler entitlements and delusions. We see it as a set of practices intrinsic to what it means to be a Christian in North America, in the wake of the legacy of colonization. Without this kind of a discipleship, our witness truly is flawed. It’s a big healing that has to happen for us as a church.

Enns: This work does not just stop at family history. It’s a compassionate and critical assessment of our community and settlement patterns that honestly faces settler myths of innocence and exhumes stories of complicity. The second part of the book explores how we work toward reparations and restorative solidarity, repatriation and understanding how colonialism has impacted us. It explores the moves to innocence that we use on a regular basis, such as, “Oh, it’s too complicated. We can’t do that. There’s no way we can give the land back.” Or, “Let sleeping dogs lie.”

Q: What should motivate churches to join in this work?

Myers: Harry Lafond is a Cree Elder in Saskatchewan, who has been extremely helpful and wise in this journey. He was the former executive director of the Office of the Treaty Commissioner. He put it so succinctly once in a conversation with Elaine, in which he said simply, “Our loss is your loss.” Ultimately, the motivation for reaching out to churches is as pastoral as it is prophetic. It’s prophetic because it raises hard truths and hard questions, many of which have been marginalized, silenced or ignored. The only way we can recover from the dis-ease of colonialism is to be in meaningful and just relations with our Indigenous neighbours. As we have seen with other forms of racism, not to face this dis-ease is to compromise the integrity of the Gospel for coming generations.

Q: Do you see the church engaging this work now? Can you give me examples of that?

Enns: Denominations across the U.S. and Canada are repudiating the Doctrine of Discovery. In the book, we share stories of how people are giving money back from the sale of their land to the Tribes whose ancestral land it is. There are expressions of reparations and repatriation among Catholics, Methodists and Presbyterians, where churches are recognizing that, as a denomination, we have benefited from this land. For example, the Jesuits had many acres in the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota and they have now returned some of it. Experiments like this are bubbling up all over.

Myers: We talk about the theological notion of repentance in our tradition: it means turning our history around to head toward healing. We’re just at that point of turning. Many examples of justice work right now are experimental, they’re partial, but they’re the next step, which will lead to further steps. One of the experiments spreading in the U.S. is the voluntary land tax. Settlers pay into a fund that goes toward Indigenous institutions. But there is obviously lots of resistance to such efforts among settlers. We live in a narrative of denial. The bulk of our book is about preparing settlers to embrace the work of restorative solidarity and reparation. We know from centuries of social change work in the U.S. that when you take a dramatic step to overcome historic injustice with whole communities, you get a backlash effect because people haven’t done the work individually, or communally, to realize why change is necessary. This book outlines a process for churches and other communities of conscience for how to do that work.

Q: Do you have wisdom to share or suggestions around taking that first step? What does it look like? Is it me reaching out to the nearest reserve and saying, “Hey, we’re a faith community that wants to start a relationship with you? How does that sound?”

Myers: We think the first step for each of us—as individuals and communities—is to understand that these aren’t issues outside of us. We are all subjects in this discipleship journey. There’s not a single one of us who doesn’t have a family story that is entangled in the history of colonization. This is our issue. It’s not just another tick on the social-justice agenda.

Enns: The Spruce River Folk Fest north of Prince Alberta, Sask., is an example of a first step. Each year, Ray Funk—who has long had relationships with Indigenous neighbours—opens up an opportunity to the entire Mennonite community to learn about federally unrecognized Indigenous Bands. There’s an auction and an opportunity to donate to the causes of justice for the young Chippewayans and Stoney Knoll. Our friend Rick Ufford Chase in Stoney Point, N.Y., and his Presbyterian church wanted to give land back. He made a cold call to the local chief and said, “Hey, can we sit down and start talking?” The chief was grateful and it turned into a beautiful experiment in repatriation. We’ve got to get over the awkwardness of stepping out there. We’ve got to show up and pay attention to what local Indigenous folks are doing and start having conversations together with them. Some of the Mennonite women involved in my research went on walks as part of the Saskatchewan TRC events. One woman said, “I decided that morning, I was going to be really brave. If there was an Indigenous woman walking, I was going to talk with her and just strike up a conversation.” She did and it was a powerful and lovely experience. We need to start trying to relate with each other.

Q: What’s your hope for this work for faith communities like Mennonite Church Canada?

Myers: We hope this book will help capacitate a renaissance in our churches, beginning with the Mennonite Church, in which we take a close, compassionate and critical look at our communal and ecclesial narratives and histories. Then to begin strategizing how to strengthen the relationships that we have with Indigenous communities. We also need to get involved in political advocacy, for example, urging Canada to fully adopt UNDRIP.

Enns: Leonard Doell was Indigenous Neighbours Director at MCC Saskatchewan for many years. One of the small things he did with his grandchildren was, every time he told a Mennonite settler story, he also told an Indigenous story. Let’s all of us Mennonite settlers learn and share stories of Indigenous peoples. They are as important to our health, identity and ability to move forward, as the stories of our church and community.

Myers: We end this book with an account of a Round Dance that Harry Lafond led us in a couple years ago. What a beautiful parable that great Cree tradition is, of being in a circle, looking at each other’s faces, moving together to music and making commitments. What do we want to see in the future? We want to see a Round Dance of recognition and reparation and maybe even reconciliation, when justice has been achieved.

Healing Haunted Histories is available through CommonWord. For more information about the book, visit healinghauntedhistories.org.

Comments

New Mission Fields

In Healing Haunted Histories: A Settler Discipleship of Decolonization (2021), Elaine Enns and Ched Myers want to expose “hard truths about settler complicity in historic and ongoing injustices perpetuated against Indigenous peoples … to work toward reparations and restorative solidarity.” Elaine Enns goes on to say that this book “tackles the oldest and deepest injustices on this continent (NA), violations of every intersection of settler and Indigenous worlds,” and that through “healing the ‘primal sin’ of settler colonialism, we (Anabaptist Mennonite Christianity) can heal ourselves” (HHH).

Enns and Myers approach to healing the primal sin of settler colonialism and injustice to Indigenous peoples, is to examine their own familial histories in the settings of the Mennonite Russian/Ukraine experience, the twentieth century Russian Mennonite immigration to Saskatchewan, and the Ventura River Valley of California where they now reside.

Enns in particular lays out an emotive family narrative of a journey of suffering which her ancestors experienced in Ukraine during the Russian Revolution of 1917, as well as the suffering her family caused by participating in the displacement of Indigenous peoples in their immigration from Russia to Saskatchewan in the early 20th century.

In HHH, Enns identifies that the Mennonite settlements in Russia post 1789, also displaced some of the Indigenous groups of the steppes, namely the Nogai and the Cossack, in a similar fashion as happened in Canada. The Mennonite historical narrative makes claim that governments (Tsarist and Canadian) were responsible for clearing the land of inhabitants, and that Mennonites were unknowing participants. Enns states of her family relocation to Saskatchewan, “they were entirely unaware of the violent Indigenous displacement only a generation before (1885 Saskatchewan) that made ‘available’ the lands they now occupied” (HHH). Mennonites in this instance are repeat offenders, and there is a definite pattern here of Mennonites usurping the lands of Indigenous peoples, a pattern established and repeated in Manitoba, Ontario, Kansas, Mexico, Paraguay, Bolivia, etc.

Enns’ narrative in HHH is a clear and strong portrayal of Mennonite complicity in the “theft of lands” from Indigenous groups in NA. Her account is generously interspersed with many Biblical references as to what a relationship between a just God and His (sic) people looks like. Enns indicates that she is committed to righting those injustices done to Indigenous groups in Canada by Mennonites through the book, hoping that Mennonite Church Canada congregations will use the book to inform themselves, and to work towards restorative justice of Indigenous issues of injustice.

While Enns portrayal of Mennonite/Indigenous injustice issues is fair, I think that her focus on righting these issues is somewhat misplaced. Enns is adamant that Mennonite Christianity is a hopeful viable medium by which the Indigenous injustices of NA in the last 500 years can be resolved, however it is clear that Christianity itself is complicit in and causal to these very injustices. The Anabaptist Mennonite Christian movement, the pattern of negotiation for and occupation of Indigenous lands over many centuries, makes it clear enough that the Anabaptist Mennonite Christian thirst for land, the pursuit of mammon, is at the very heart of these injustices.

I think that rather than focusing on issues of Indigenous injustice at the hands of Mennonites, Enns would be better served to focus on the history of how an apostate Mennonite church has refused to hear and obey the word of their God of justice, a church which time and again has sought to flee to another country after having been disciplined by their God for the pursuit of mammon, for wealth accumulation, for the worship of the “golden calf.”

Rather than embark upon another “mission” to help Indigenous groups, I believe Enns needs to turn her prophetic voice and mission efforts towards Mennonite congregations, to sit on the church steps in sackcloth and ashes, until an apostate Mennonite church repents and turns back to their God of justice. The “mission field” now is not in far-flung Africa, or even with Indigenous peoples, the mission-field is here in our own houses of worship, where we on one day give lip-service to one God with hymns and prayers and worship the idols of mammon the rest of the week.

Refocusing her “mission-field” from Indigenous injustice issues, and onto being a prophetic voice calling Anabaptist Mennonite Christians to repent from apostasy, will indeed help Indigenous peoples in the long term.

Peter Reimer

Gretna, Manitoba

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.