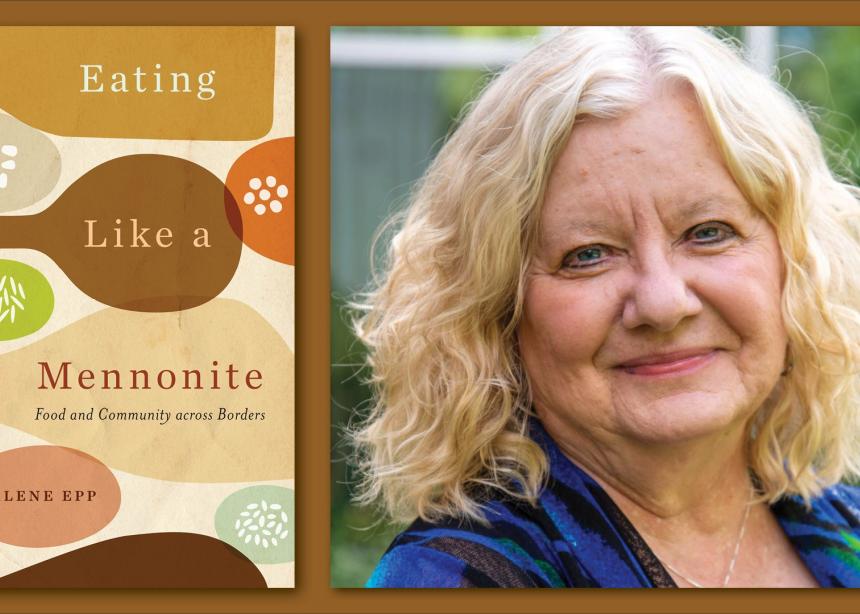

In her new book, Eating Like a Mennonite, Marlene Epp addresses the question of whether there is such a thing as “Mennonite food.” She assumes there is, and declares it should be celebrated, disagreeing with those who say “Mennonite” is a religious label that should not be used as an adjective for food.

Food and spiritual traditions are closely related, says Epp, and “religious belief and practice are embedded in culture.” Eating traditional foods connects us with the past, thus shaping our memory and identity.

When she talks about her own tradition, she uses multiple examples of Russian Mennonite foods that evoke nostalgia and connection to her family and faith community. Foods such as zwieback, rollkuchen, borscht, vereniki and peppernuts remind her of who she is and her connection to her ancestors who lived in what is now Ukraine. She talks about “the role of food in personal and group identity.”

Today, the Mennonite church around the world includes people of many ethnicities. To avoid being exclusionary, Epp argues that we need to broaden our concept of Mennonite food to include the cultural foods of everyone who identifies as Mennonite or Anabaptist, wherever they live around the world. Epp includes observations from her travels to India and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Celebrating all cultures can be a unifying factor.

Certainly Epp is right that there is a connection between food and identity in the Russian Mennonite context. I remember being surprised at the emotion with which my former pastor, a Russian Mennonite, would speak about his mother’s zwieback and platz. Online photos of items such as paska and zwieback result in numerous instinctive responses, suggesting that these traditional foods carry special power.

However, for those of us descended from Swiss Anabaptists, it is not clear that food plays a similar role. Epp works hard to mention foods that she assumes will evoke emotion in our tradition, but sauerkraut and shoofly pie just don’t do the trick. These are foods that outsiders have told us define who we are, but in my experience, they are not foods we associate with our families or faith community.

Epp mentions David T. Martin, a Swiss Mennonite church leader from Ontario, who declared in 2017, “no more Mennonite cookbooks,” because he didn’t want cultural baggage connected to the term “Mennonite.”

Epp’s response is that food and faith are connected; it’s impossible to avoid the cultural baggage. But the idea that there is a deep connection between faith and food is foreign to Swiss Mennonites. In 2011, in Canadian Mennonite, Martin wrote that, “there is nothing ‘Mennonite’ about the foods we eat.”

Are those of us who are Swiss Mennonites missing the faith and food connection because the right foods have not been identified? Have food memories become so individualized over time that we have lost a connection with the religious community? Or are the cultural histories of the Swiss and Russian Mennonite traditions simply different, such that food has a connection to faith in one but not the other?

Beyond the question of “Mennonite food,” Eating Like a Mennonite includes much more about how food has impacted Mennonite life. Epp provides a useful exploration of the role of cookbooks, suggesting that even during times of modernization and acculturation, “published cookbooks served to reinvigorate collective cultural identity.”

She also looks at how food has impacted the role of women in Mennonite culture and the effect of food scarcity in those who survived.

Epp points out that eating together builds community, commenting that, “in many congregations, potluck meals are akin to religious observances.” Food is a unifying force, she says. “At a food sale, Mennonites from diverse backgrounds and with diverse languages, histories, cultural customs, and worship practices find common ground.”

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.