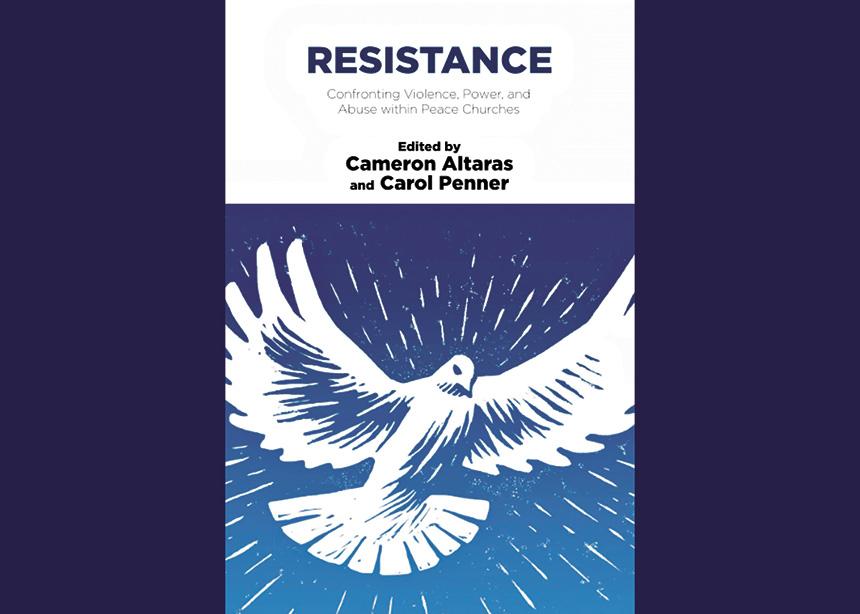

Over the past several decades, a particularly painful and dissonant question has arisen within the Mennonite church: What is a faithful response to violence perpetrated by the church, especially one that professes to be a peace church?

This diverse collection of essays, poetry and personal reflections helpfully grapples with this question from multiple angles and perspectives, with a focus on the violence of colonialism, racism, homophobia/(hetero)sexism (Part 1), and sexual violence and abuse (Part 2).

Editors Altaras and Penner frame this conversation in terms of a shift in the guiding metaphor of Anabaptist-Mennonite peace theology and practice, so that the traditional emphasis on nonresistance to violence (based on the Sermon on the Mount, Matt. 5:39) becomes one of resistance.

In their words: “We use resistance in our title to pay tribute to the power of survivors of evil and immoral acts of violence, abuse and betrayal. It is not a rejection of nonresistance, but a hope of creative interaction with the tradition. . . . What might it mean, therefore, to practise love for one’s enemy and at the same time resist evil and seek healing for those affected by the resultant harm?”

The strengths of this collection lie in the rich diversity of perspectives and experiences to which it gives voice, centring those—queer, female, Indigenous, people of colour—who have long been on the “underside” of the Anabaptist-Mennonite tradition.

Highlights for me were the moving personal conversation between Lydia Neufeld Harder and Ingrid Bettina Wolfear regarding the Sixties Scoop; Pieter Niemeyer’s account of resisting “erasure” as a queer Mennonite pastor; and Ruth Krall and Lisa Schirch’s respective chapters on the circles of harm and re-traumatization caused when the community or institution fails to believe and support a victim-survivor of abuse, which provide crucial insights for congregations and church institutions.

Several chapters helpfully complicate key narratives that shape Anabaptist-Mennonite understandings of abuse, from the reification of self-sacrificial enemy-love in the story of 16th-century Anabaptist martyr Dirk Willems (Kimberly Schmidt), to the belief that all broken relationships can and should be mended (Elsie Goerzen), and to the assumption that Mennonite communities are “power-neutral and therefore incapable of abusing power” (Kimberly Penner).

Sarah Ann Bixler’s exploration of the (short) history of Mennonite women’s head coverings as a symbol of women’s submission and their quiet fall into disuse was also noteworthy. What emerges from this diversity is a sense of the multi-faceted nature of this issue, the need for truth-telling and a recognition of the church as it is rather than only as we envision it theologically, and the need for this work of resistance and healing to be engaged from multiple angles.

Precisely because of its diversity and length, the collection would have been strengthened by being organized into more specific topics or sub-headings. Also, although several of the chapters point beyond individual, church or institutional experience alone, a more thorough look at restorative justice practices, the double-edged relationship between victim-survivors of abuse and law enforcement, and socio-political engagement and advocacy for survivors of abuse, would have enriched the collection further.

The book is pre-eminently practical and ready for church groups, university and MDiv students, and pastors to apply to their own contexts, including poetry and prayers for reflection and worship. I find it significant that as I write this, Sarah Polley’s screenplay adaptation of Miriam Toews’s novel, Women Talking, which likewise delves into themes of sexual abuse, faith and peace in Mennonite communities, has received an Academy Award and numerous accolades. This suggests a deep hunger within and beyond Anabaptist-Mennonite communities for these experiences of violence to be overtly named and resisted.

Resistance is a welcome contribution to this ongoing conversation and peace practice.

Susanne Guenther Loewen is a Mennonite pastor-theologian and university instructor in peace studies.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.