I had to make my way past the sombre line-up of people waiting for welfare cheques at the band office. It was awful. I worked in the office of a northern first nation, and once a month I had to squeeze past the indignity, shame and hopelessness that silently clogged the front entrance.

That highlighted two things for me. First, welfare is not a solution; it is a dreadful lack of creativity. Never did I think “the solution is bigger cheques.” Second, people need jobs, with exceptions for those who are unable to work.

I viewed unemployment on remote first nations as hopeless. But Shaun Loney sees it completely differently. He sees through the problems to the opportunities. For all the government leaders who speak about creating jobs—almost as if their intentions will magically turn into sunnier employment stats—Loney knows how to do it.

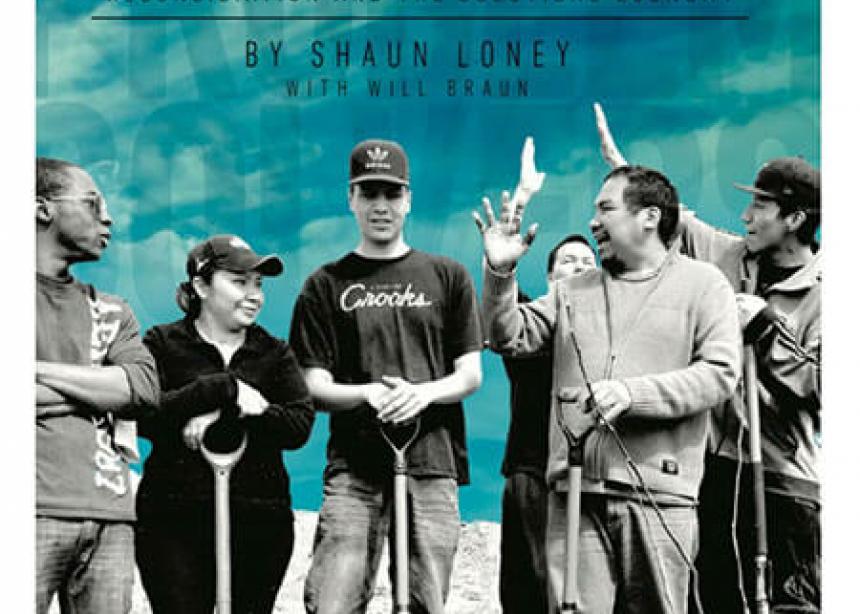

For a decade, he has been a leading developer of social enterprises, largely among indigenous people. In his new book, An Army of Problem Solvers: Reconciliation and the Solutions Economy (armyofproblemsolvers.com), Loney shares his intensely practical vision of economic reconciliation.

Reconciliation is a hot topic, and I confess that much of the reconciliation talk I hear leaves me feeling blank. Too often, it feels like a continual refinement of the articulation of problems. I hear some talk about solutions, but too often the solutions are symbolic (art projects), intangible (building relationships), or uncreative (more government money). All of these are unquestionably important and all of them leave me unsatisfied.

The vision in Loney’s book is different. And that is why I was so grateful for the chance to help edit the project. The gist of Problem Solvers is well-suited to the Mennonite ethos. We are practical people; we care about doing good; we are community-oriented; we appreciate thrift and industriousness.

The book focusses largely on social enterprises, which it defines as “smaller-scale community businesses that use market forces to solve stubborn social or environmental challenges.” They combine business smarts with “community rootedness” and “basic human caring.”

I see two underlying social enterprise strategies. One is to identify waste and turn it into opportunity. A Mennonite Brethren Church in St. Catharines, Ont., is involved in a project that uses B-grade fruit from surrounding farms—fruit that would otherwise be discarded—to make jams and preserves. The project employs largely people who were previously homeless. It is not a charity. It is not a government program. It is a community-oriented business. It turns waste into jobs. It also saves the government money, because people who used to be heavy users of social services become healthier and more self-sufficient.

Another category of social enterprise involves strategies to make better use of existing expenditures, whether government spending or the money that already circulates in poorer communities. When Loney saw the welfare line at the Garden Hill First Nation, he saw opportunity. People get their cheques, then go down to the bank to catch a water taxi to the Northern Store on a nearby island. The Northern Store, which operates as a monopoly in many remote communities, sells a wide range of food and other products. Its goal is profit.

Eventually, the people of Garden Hill set up a five-hectare farm and a local market to compete with the Northern Store, and they took over the canteen at the arena. The fact that their customers don’t have to pay the water taxi fee gives them an advantage. And they sell healthy food, which is critical in a diabetes-ravaged population. The money already spent on food in the community can be spent in ways that employ locals and promote health, instead of going to distant shareholders.

The kicker is that the federal government subsidizes a carrot that the Northern Store brings in, but not one grown locally. The subsidy only applies to food that is shipped by air. Existing government spending could be directed in ways that would be far more effec-tive, reducing welfare and health costs, instead of buying aviation fuel.

The federal health minister’s interest was clearly piqued when I asked her about this in an interview. The minister of indigenous affairs has since visited the farm at Garden Hill.

Problem Solvers is full of other real-life examples of reversing colonialism and bringing tangible reconciliation.

Mennonites belong on the forefront of doing good. That should include a deep dive into the realm of social enterprise, gently offering start-up capital, ideas, business savvy, connections and caring companionship.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.