Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) is the largest and most influential Anabaptist organization in the world. It has nearly 1,200 workers and an annual budget of $82 million. Its reach extends to 62 countries abroad, and here in North America it encompasses 14 denominations, covering the spectrum from Amish grandmothers to the Meeting House, a Brethren in Christ church that is Canada’s coolest mega-church and a major MCC supporter.

MCC’s publication, A Common Place, goes to more than 75,000 people—that’s more than Canadian Mennonite, MB Herald, Mennonite Weekly Review and The Mennonite combined.

And the organization drew more than 16,000 Canadians to volunteer at its stores, relief sales and material resource centres in the past year.

The fact that MCC is so prominent says much about who we are as Mennonites. We are not centred around an academic institution, a geographical location (like the Vatican), a leader, or even our church conferences. Rather, the closest we have to a core is a collective, practical expression of Christian care. We are people who help, and much of our helping is done through MCC.

For the many of us who have lived in huts abroad, sorted blouses at thrift stores, sold pies at relief sales, written cheques or otherwise invested ourselves in MCC, the organization is close to the heart of what it is to be Mennonite. It creates commonality among North American Mennonites and it connects us to the rest of the world.

Given the centrality of MCC, its four-year re-visioning process should be of interest to us. The New Wine/New Wineskins initiative, which started in 2008, has brought together a total of 2,000 people from 50 countries at 60 meetings to give input to the evolution of MCC.

To date, MCC has invested about $850,000 in its effort to make the process as thorough and broad as possible. That money is split between consultants’ fees and travel, with the latter making up the larger chunk. Staff time is not included. For perspective, the $850,000 figure is more than the total donations received for flood relief in Pakistan and is enough to fund the Bolivia program, with 39 staff, for a year.

Although the likely outcomes of the process are fairly clear, and the consultation phase is over, final decisions have yet to be made, and implementation is only expected to be completed in early 2012.

Behind the scenes

From the beginning, Wineskins was a two-headed process. One major issue was how to make MCC more accountable to international partners. “The people who you’re trying to help ought to have a say,” says MCC binational director Arli Klassen. Wineskins sought the best way to include the vast array of international partners in decision-making in a more thorough way than is currently the case.

The other issue at play has been how to “make more space for national differences between Canada and the U.S.,” to use Klassen’s words. That’s code for the fact that the Canadian branch of MCC is eager to oversee more international programming from Winnipeg, Man., instead of sending two-thirds of the money raised in Canada to Akron, Pa., where most administration of international programming now happens. (Roughly half of overall MCC income is generated in Canada). It’s also code for the fact that MCC in Canada accepts millions in government money, while MCC in the U.S. has a staunch tradition of not accepting government money, and thus keeping its distance from American foreign policy.

In addition to these two divergent issues, other agenda items included strengthening MCC’s ties to churches at home and abroad, and finding better ways for the provincial, regional and national MCC offices to coordinate decision-making.

These cross-currents created some muddy waters. And the lack of a clear, single focus may have had something to do with the fact that Wineskins did not become a hot topic in the broader Mennonite community. For instance, Canadian Mennonite received only two letters to the editor on the topic and one was from an MCC board member. Nevertheless, the process was important.

Two main outcomes have emerged.

First—and this one admittedly deals with the sort of institutional shuffling that consumes administrators and confounds the rest of us—MCC’s Canadian office will most likely be granted its wish to administer a significant proportion of MCC’s international programming from Winnipeg, in addition to the smaller pieces of that work it already does.

In simple terms, as a result of some cross-border administrative jostling, considerably more of MCC’s programs will be overseen from Winnipeg, instead of Akron. Little will change from the standpoint of MCC supporters or the people MCC works with abroad. And MCC’s provincial and regional offices will not undergo significant changes. “We’re not changing what we do, but how we do it,” Klassen says.

In insider lingo, the working proposal is that MCC Binational be disbanded, with its work given over to MCC Canada and MCC U.S. These two branches of MCC would maintain their own boards, but would work collaboratively and with a single identity overseas. A new council would oversee overall governance of MCC, guide the vision, set standards, and “protect MCC’s brand,” says Klassen. The council would have as few as seven members—including MCC Canada and MCC U.S. representatives, as well as church and international voices—and no more than five staff in a location as yet to be determined.

Theoretically, the shift would facilitate smoother and closer relations between MCC’s Canadian office and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the federal government’s foreign aid department, although changes at CIDA may mitigate this trend. MCC Canada director Don Peters says the CIDA factor has not been a “driving force in the Wineskins process.”

MCC’s provincial and regional boards, as well as the denominational conferences that ultimately “own” MCC, will have a role in approving changes. The approval process and the numbingly complex task of figuring out how to divide the work between Canada and the U.S. are expected to take much of 2011.

Ron Mathies, who served as MCC binational director for nine years, suggests three questions for assessing the value of the re-organization:

- Will international program delivery improve or become more complex due to duplication and conflict?

- Will MCC’s profile, support and witness in Canada and the U.S. increase or decrease?

- Will MCC remain one organization, two, or many?

Mathies suggests it will take “a couple of decades” to see if the re-organization proves wise. In the meantime, he expresses “great faith” in the broad MCC community. “It’s the peoplehood,” he says, “who pull things out of the fire,” when necessary.

The rich help the poor

The more interesting Wineskins issue is about “what it means to be globally accountable in today’s world,” to quote Klassen. How can the people most affected by MCC decisions be more a part of those decisions?

The matter could be framed more broadly. Being a rich and powerful North American organization creates an awkward imbalance between the helpers and those who are helped. Although our faith emphasizes simplicity, sharing, equality and humility, we in North America remain far richer than the people we help, and in some ways we remain above them. The Wineskins question about global accountability was an impor-tant way of grappling with the inherent awkwardness and complexity of the rich helping the poor.

“Our temptation is to think of ourselves as possessing what other people need,” says Earl Martin, who served for 25 years with MCC. There is some truth in this, of course, but how can we have authentically mutual relationships with sisters and brothers around the world when we are always the helpers and they are always the helped? This imbalance of roles can lead to self-importance on our end and erosion of dignity on the other.

This complexity is not new to MCC. When the MCC Africa department consulted African colleagues in 1993, the resulting report said that “the old ‘fixing/saving/meeting human need’ paradigm [should] be subsumed and transformed under a larger paradigm of building global community and particularly global church community.” The current questions about accountability are part of an ongoing quest for a more genuine equality in a world of gross inequity.

Globalization of MCC

In this context, a fundamental re-shaping and “globalization” of MCC was on the table from the beginning of the Wineskins process. One of the main models considered was for a variety of overseas Anabaptist service agencies to come together under the MCC umbrella, with the expanded global MCC possibly being based outside North America.

This general concept was on the table when 27 Anabaptist church and service groups from 18 countries met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, last August. While the gathering, which was convened by Mennonite World Conference (MWC), was not part of the Wineskins process per se, the potential globalization of MCC was a primary factor in discussions.

In a decision with considerable consequence for the history of MCC, the global organizations at the gathering opted not to be part of an expanded MCC. “People were very grateful to MCC,” says Pakisa Tshimika, MWC’s global church advocate, but they did not want to “take MCC and turn it into a global entity.” The groups decided to work towards greater collaboration within a formal network, but they did not want to become “little MCCs,” says Tshimika. They did not want MCC to globalize in the way it had been considering.

It was a sobering moment for MCC. But the organization seems to have taken it well.

“It was humbling to be told we are not the centre of the Anabaptist service world,” Klassen says. The new global network is “not going to be within MCC [or have] an MCC identity,” she says.

Don Peters, who was also at the consultation, says some people within MCC were disappointed, but upon reflection there was recognition that the direction given in Addis Ababa is “an appropriate post-colonial way to go global.”

Similarly, Klassen admits that it was “pretty ethnocentric to think that others would want to become part of MCC.”

Tshimika, who is from the Democratic Republic of Congo, uses the word “imperialistic” to characterize the MCC-centred option that was rejected.

While MCC is a central body for North American Mennonites, it turns out it is not the central committee for the global Anabaptist community. Ironically, at the Addis Ababa meeting, MCC’s position of wealth and prominence was a disadvantage as much as a strength.

Tshimika is clear that the decision of the group was not a rejection of MCC itself—which received affirmation—but of the approach it had been considering. He says MCC took the message “very seriously.”

So MCC will not “take on an entirely different shape,” a hope Klassen expressed in 2008. International representatives will likely be added to the MCC Canada and MCC U.S. boards, and the global entity envisioned at the Addis Ababa consultation will provide another element of international accountability, but MCC will remain a North American organization, something MWC had actually been advising for years.

Elephant and mouse

Mathies says that in terms of MCC’s global accountability, the key question now is the future relationship between MCC and MWC. The latter represents 99 Mennonite and Brethren in Christ national churches from 56 countries, and is the only Anabaptist body, Mathies says, with a truly global mandate. But despite its unmatched mandate, it is dwarfed by MCC in terms of budget and capacity; MWC’s annual budget is $1.4 million and it has 26 staff, 22 of whom are based in North America or Europe.

Tshimika uses the elephant and mouse metaphor to describe MCC’s prominence in the realm of global Anabaptist organizations. Despite this imbalance, he says that in Addis Ababa, it felt like “everyone was on the same level.” This speaks to the potential for MWC to create a forum in which MCC can practise genuine mutuality.

Although the global Anabaptist church, in the form of MWC, provides the most logical forum of international accountability for MCC, it also has limitations. First, not nearly all of MCC’s overseas partners or aid recipients fall under the MWC umbrella. MWC cannot represent MCC partners who are not Mennonite or Christian. A further limitation is expressed by some people within MCC who feel closer ties to MWC would mean that in certain circumstances MCC would give preference to MWC-affiliated partners, rather than non-Mennonite partners that may be better suited to particular initiatives.

In a presentation at MCC’s 90th anniversary this summer, Mathies articulated something of this tension by asking, “Will MCC try to become a more effective NGO, or will it serve the church?” Stated differently: Is the mission of MCC to raise as much money as possible, and help as much as possible, or is it to foster mutually enriching exchange between the two halves of what Mathies calls MCC’s “two-fold constituency” (the North American donor churches and the “program partners and participants around the world”)?

Surely the answer is some of both, but sometimes the two conflict. For example, an effective way for MCC to maximize donations is to tell feel-good, non-complicated stories that cast North Americans as noble helpers—stories that say, in essence, “look how great it is that you made a difference by helping.” But such stories maintain the divide between helper and helped.

A humble, unifying role

While MCC sometimes feeds this divisive noble helper identity among its supporters, it also has an outstanding record of fostering unity and exchange among an exceptional diversity of people. This ability is surely one of MCC’s greatest strengths, more unique and impressive than its fundraising ability. Perhaps MCC can address the global accountability question, which is also a question of authentic human equality and mutuality, not only by adjusting organizational charts, but by doing more to show North Americans how much the rest of the world has to offer them.

Both Mathies and Martin are most passionate when speaking about how the different parts of MCC’s two-fold constituency “desperately need each other,” as Mathies puts it. He says people “in the Global North have material resources and those in the Global South have spiritual resources that require exchange for their mutual benefit.” Martin says that while we are called to share what we have, “just as strong or stronger is the call or opportunity to listen to and learn from people of other cultures.” This requires that we “take a humble stance.”

While MCC has always been good at listening and learning, the Addis Ababa gathering called the organization, and, by extension, its North American supporters, to a deeper humility. Part of the lesson was that the awkwardness and complexity of its role as the “elephant” will not be done away with by simply globalizing organizational structures. A shift in posture here at home may be the more important factor.

Klassen says that in Addis Ababa, MCC personnel were challenged “to let go of some of [their] ideas.” Perhaps that also captures what MCC’s North American supporters can take from the Wineskins process and the Addis Ababa gathering. We need to let go of the tendency to see ourselves primarily as helpers, fixers and possessors of what others need.

We are indeed people who help, and we must help generously and competently, but, more importantly, we must also be people who recognize the complexities of helping and the need to be humble recipients.

Will Braun served for five-and-a-half years with MCC in Brazil, B.C. and at the Winnipeg office. He attends Hope Mennonite Church in Winnipeg, Man., and can be reached at wbraun@inbox.com

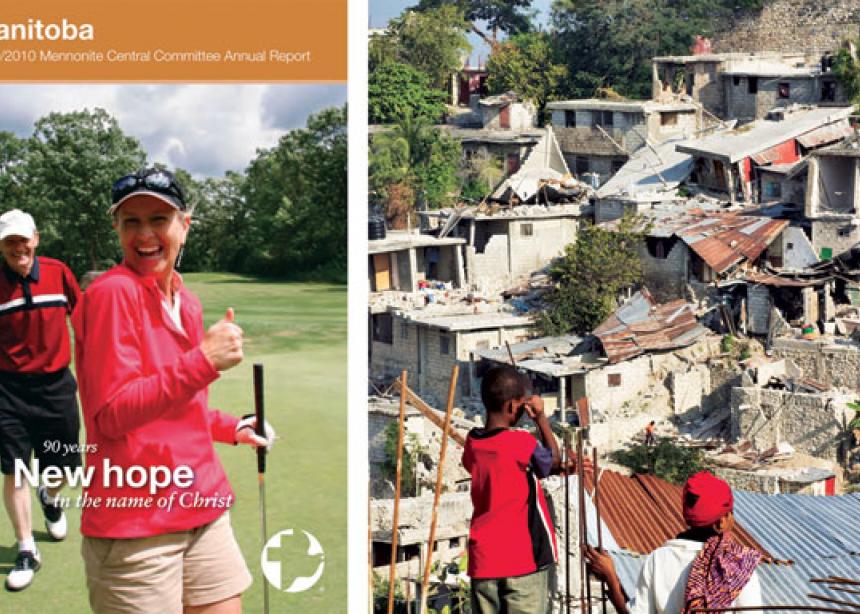

The MCC revisioning process seeks to address the tension of being rich Christians in an age of global inequality—an age in which golf tournaments in Manitoba (as shown by the cover of MCC Manitoba’s annual report, left) fund hurricane recovery efforts in Haiti. (MCC file photo by Ben Depp, right)

Comments

"Similarly, Klassen admits that it was “pretty ethnocentric to think that others would want to become part of MCC.”

"Why can't I join MCC and serve in another country?" I clearly remember a dynamic Mennonite young adult asking me this question when I served with MCC in Indonesia. It has been wonderful to see the Yamen program expand in recent years. Back in the 1970's an Indonesian family served with MCC in Bangladesh. Currently, a number of Country Representative positions are held by leaders of non-North American origin. MCC is more multi-national than it was in its early years.

The phrase, "The groups decided to work towards greater collaboration within a formal network" stands out to me. It deserves to be held in tension with the international rejection of "the approach" MCC had been considering.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.