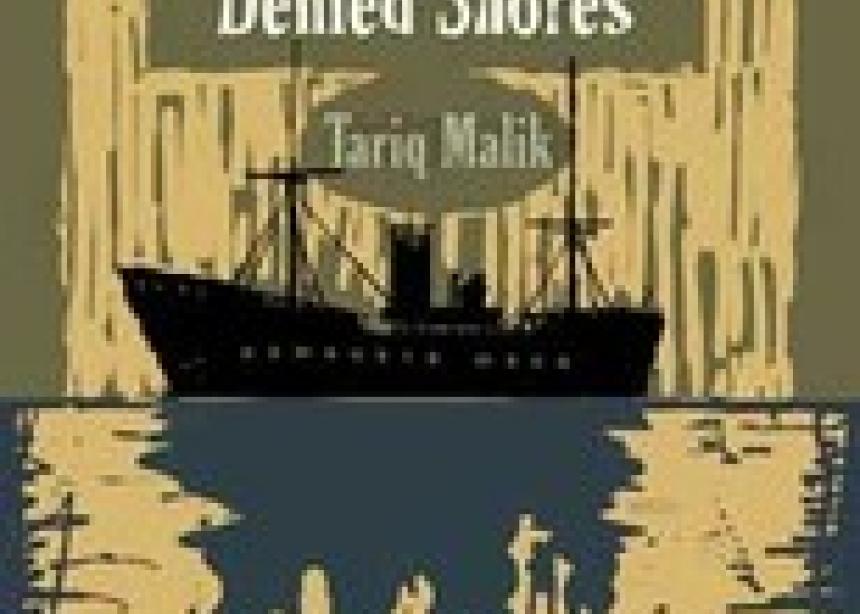

Just released in Canada Chanting Denied Shores by Tariq Malik is a book I have been waiting for. This is an historical novel based on the true story of the Komagata Maru, a ship carrying 376 Indian immigrants who were denied permission to land in Canada.

This happened in 1914 at Vancouver’s harbour. Canada, like India, was a part of the British Empire. London at the time gave the right to any British subject irrespective of his/her religion, race or creed to settle in any of the many British colonies and dominions.

However, the reality on landing made a mockery of this right. The humiliated, thirsty and famished brown immigrants aboard the Komagata Maru had to turn back after two long months of waiting off shore. The law of the White Supremist ruled, as Gandhi was to discover on landing in South Africa. Earlier in 1907 violence led by Europeans had erupted in what’s recorded in Vancouver’s history as the first ‘Race Riot’.

The irony was that some of the would-be-immigrants on the shiphad fought for the Empire. They were soldiers willing to die again for the King. They were denied what their counterparts, the white British soldiers, were offered – land and jobs in the colonies and dominions. The Indian soldiers were all dressed up in British army uniforms, shining medals of bravery on their chests and stripes of service on shoulders ready to set foot on their King’s kingdom called Canada.

After two months of frustration, humiliation and anger they plucked off their badges and flung them into the Burrad Inlet as Komagata Maru was shoved out of the Canadian Waters by an armed navy ship. In Chanting Denied Shores there is a chapter titled ‘Battle of Burrad’. The stranded Indians, hoping to be immigrants, did not give up without a fight when armed men in boats approached Komagata Maru and attempted to attach ropes to tug it out of the Burrad Inlet :

… men use axes to swiftly chop down the tug’s grappling lines. Others begin to hurl showers of coal, firebricks, clubs, iron bars, hatchets and other missiles onto the exposed and crowded tugboat deck. They manage to injure several of their adversaries in the very first few minutes of the engagement. A number of police helmets have tumbled into the water, and at least one police officer has been knocked down onto the deck. Others have been injured by blows to the head.

The Empire’s discriminatory laws perhaps led to its downfall. In her latest book called Day of Empire (Doubleday: 2007) Amy Chua explains that Empires fell when diversity within sparked conflicts because its subjects were excluded. But Empires strengthened and lasted longer when the subjects were respected and included as equals. Conflicts often result from hate and often hate is fired by humiliation – of a people’s race, culture, religion or any other value or habit that they cherish with pride of tradition. Avenge for the humiliation suffered has long been the cause of social and political discord in human history.

Chanting Denied Shores is a narrative about how the Greater Indian Diaspora came to be through continuous struggles for justice. The book contains accounts of fortitude and resilience in face of the humiliation of Indians seeking dignity and justice in the English Raj.

For example, there is a narration about five of the passengers aboard the expelled Komagata Maru who defied the racist stance of English Canada by returning via the backdoor. The five determined fellows boarded a ship in Japan and landed far south in Mexico and then travelled on foot via the Rockies following the railway tracks so they would be not be detected and shipped back to India. Unfortunately, only three of the five survived the gruelling journey and were able to sneak into British Columbia from Alberta.

Their grandchildren live in Vancouver to tell the tale. In the process of defying the ban these men created a legend of human perseverance and courage. These stories connect with stories of struggles of Gandhi in South Africa and with the many campaigns fought with moral stamina around the British Empire from the Indian Ocean territories to those in the Pacific and the Caribbean.

Of particular interest in the saga of Komagata Maru is that it was linked to the political awareness through the Ghadar Party newspaper that was printed on the Pacific Coast of North America and read within the Diaspora by our forefathers in East Africa, South Africa, the Philippines, Fiji, the Caribbean and Burma. Today, these newspapers have become a substantial part of Indian Clandestine Literature. (A recent conference was held in Berkley, California, on the importance of Clandestine Literature in promoting human and civil rights. No Indian literature was represented!).

It would be fascinating to see a map of the world between 1910 and 1947 showing the route of the Ghader Party newspaper flaming awareness wherever it was read and discussed. “Freedom Movement’ was the quiet talk in the Indian bazaars, social prayer halls, in mills and on plantations. There was also awareness for intensifying self help volunteering efforts like building of community schools and organizations that included joint resistances, protest marches, worker defiances and strikes that are often the foundations of labour movements and seeding the civil societies.

The Vancouver Gurdwara in 1910s was all this and the only evening learning centre for the brown workers – Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus. (On Komagata Maru there were 340 Sikhs, 24 Muslims and 12 Hindus). What is also of interest is that the Sikh plantation workers in California and mill workers in Canada around at the dawn of the 20th Century were saving their hard earned wages to build girls school in Punjab. Volunteerism, unity of all communities and women’s education was the spirit of the Freedom Movement that mirrored the face of an independent secular India that the workers of the Diaspora aspired. The massacre at Jalianwala Bagh on April 13, 1919, brought them even closer and more determined to work during the day and study at night In the evenings they also planned and hoped for a better tomorrow.

I hope Chanting Denied Shores will help expand and bring forth unheard episodes from memories of the struggles of South Asian families in the old colonies and dominions. Our veterans in the Diaspora may even be able to tell us more about the Ghadar in Africa and other former British colonies. Some may be personal and family stories that we have not heard before. I remember my mother telling me about the hangings of Indians in 1917 in Mombasa, Kenya and then in 1943 in Nairobi.

Mewa Singh was executed in Vancouver for the assassination of Mr Hopkinson, the Chief Immigration Officer who denied the passengers of Komagata Maru to land. A hall in the Sikh gurudwara in Vancouver honours Mewa Singh with his picture and name. My mother also spoke about Makan Singh who worked for workers’ rights in Kenya. Now there is detailed biography of Makan Singh by Zarina Patel of Nairobi. Neera Kent Kapila’s book Race Rail and Society: Making of Modern Kenya (about to be launched in Nairobi) has new information on numerous Indian worker strike committees and protests against denied rights.

The Indian workers in Kenya were probably connected in some ways with the worldwide dissent against injustices of the Empire and in that with the working class movements outside the Empire. They would be contemporaries of the Indian workers organizing dissent for justice on the Pacific shores thousands of miles away. Or fighting individually for civil rights like Bhagat Singh a decorated soldier in the US army who was denied US citizenship (1892 – 1967) and Dalip Singh Saund (1899 – 1973) who was similarly denied US citizenship, who became a politician and fought for Indian immigration to the USA to be free and fair.

These stories laid down the paths that opened the frontiers of the Diaspora and gave Indians longer visions. They help one to appreciate the arduous journeys for equality and justice in North America and in that the role of Indians in the greater efforts for civil liberties on the continent. In that too they inspire today’s dual citizens and NRIs (Non resident Indians) to help sustain secular civil institutions towards greater pluralist, non racial and multi religious societies in South Asia the way they would like to see and enjoy living in democratic and secular West. The way they would not like to be humiliated as minorities because their race, religion, values and habits are not ‘mainstream’ where they live.

For those in the Diaspora of the ‘Third World’ connecting with the histories of national labour movements and civil societies would inspire support for the ongoing struggles for democracies and accountability of leaders so as to lessen top level corruption and inequalities due to ethnicities and wealth.

Tariq Malik shows that the desis abroad have contributed more than labour and trade to the Empire. They have been contributing to the intellectual history of the world through an underground network of literature and storytellers. That would be written about in the Comprehensive History of the Indian Diaspora or perhaps one with the title like Indian Resistance and Fight for Civil Rights in the Diaspora. Chanting Denied Shores will be a chapter in that book.

Sultan Somjee, an associate at the Centre for Dialogue at the Simon Fraser University in western Canada where he gives workshops on "Artifacts of Dialogue," is a Kenyan Asian who is promoting peace-making between East African tribes in conflict. Head of ethnography at the National Museums of Kenya from 1994–2000 he has been lecturing at the University of Nairobi. In 2001, he received the award of the "Unsung Hero of Dialogue among Civilizations" which has been presented by the UN to only 12 individuals worldwide. In 2002 he was honoured by the Interfaith and Survivors Committee of the Slums of Nairobi, with the title of Cultural Ambassador of Peace in recognition of his work during the ethnic killings. Working briefly for Mennonite Central Committee, he holds a PhD from McGill University in Anthropology and Education in the Arts.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.