Have you heard the Bible recently? Not read it, but listened to it—heard the words of Scripture, not just seen them on the page.

We don’t hear the Word of God much anymore. The public reading of multiple texts and longer passages of Scripture is not a key part of many worship services these days. This is a big change from how Christians in earlier times interacted with Scripture—and a big change from the world of the King James Version of the Bible.

‘It lives on the ear’

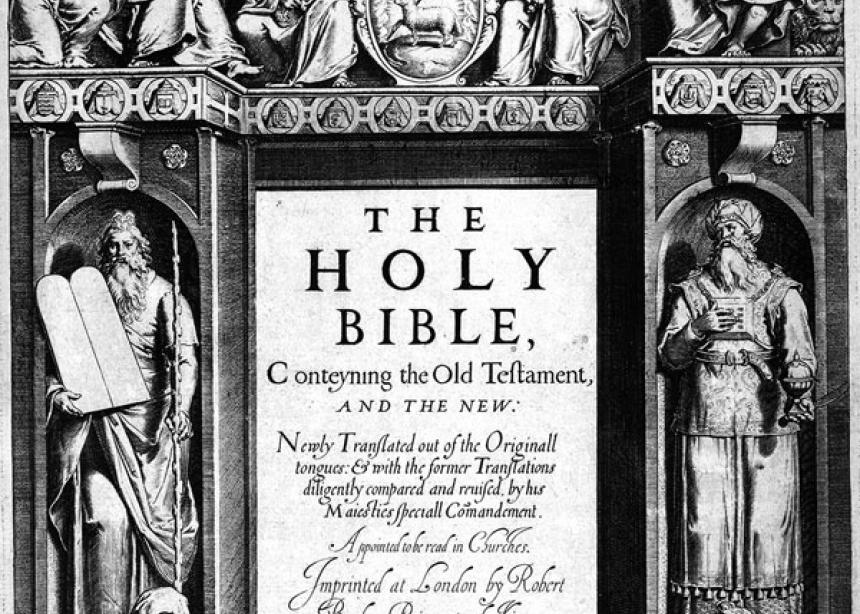

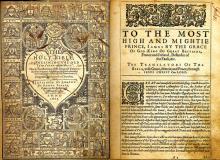

This year (2011) marks the 400th anniversary of the first printing of the King James Version—the most widely published text in the English language, and one of the most influential Bible translations ever undertaken.

Superlatives for the KJV, as it’s known, abound: “The greatest work of prose ever written in English,” “The most beautiful book in the world,” “The most important book in English religion and culture,” one of the “books of the millennium.” It’s considered by many to be a literary classic.

What gave the KJV its longevity and memorability? It’s not the quality of biblical scholarship or the accuracy of translation. Later Bible translators not only had far better access to source manuscripts than their 17th-century counterparts, but also a better grasp of the vocabulary and grammar of ancient languages.

The reason the KJV still lives on for so many today lies in the elegance and beauty of its language—the way it sounds.

“It lives on the ear, like music that can never be forgotten, like the sound of church bells, which the convert hardly knows how he can forgo,” wrote 19th-century theologian F.W. Faber.

It has a “rhythm, balance, dignity and force of style that is unparalleled in any other translation,” adds Daniel B. Wallace, professor of New Testament at Dallas Theological Seminary, Tex.

Adam Nicolson, the author of God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible, points to its “grandeur of phrasing and the deep slow music of its rhythms.”

The beauty and elegance of language in that translation was not accidental. It was, in fact, one of the primary goals: to produce a Bible with the appropriate dignity, majesty and resonance required for the public proclamation of Scripture.

Hearing the Word

The public reading of Scripture has been an essential part of worship from the earliest times. It goes back to the very first corporate worship service recorded in the Bible: the gathering of the people of Israel at the foot of Mount Sinai after their escape from Egypt. There, Moses read aloud the Word he had received from God, and invited the people’s response: “All that the Lord has spoken, we will do,” they said.

This was more than a service of worship. It was the beginning of the covenant relationship. And in the centuries that followed, the continued public proclamation of God’s Word was an essential and ongoing feature of that relationship (see Deuteronomy 31, Joshua 8, II Kings 22-23 and Nehemiah 8).

The same was true later in the synagogue. There, the public recitation of Scripture was at the heart of every worship gathering. Great care was taken in how Scripture was presented. It was never just read in an ordinary voice, but chanted. The scrolls used in worship purposely contained no punctuation or musical cues, making careful advanced preparation by the readers essential.

Early Christian worship inherited this emphasis on the public reading of Scripture—both traditional Hebrew texts and, over time, uniquely Christian writings. The writers of the New Testament epistles assumed their letters would be read out loud in the congregation (see Colossians 4:16, I Thessalonians 5:27 and Revelation 1:3). And the readings were not brief. In the early second century, Justin Martyr wrote: “The memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits.”

Early believers were not readers of the Word. They were hearers. Their experience of the texts came through the ear, rather than the eye. Most would never have seen the biblical texts at all.

For one thing, many Christians were illiterate. It is estimated that less than 10 percent of first-century Christians would have known how to read. In addition, the biblical texts were hard to get; copies were rare and had to be re-written by hand. For the vast majority of Christians, their only encounter with Scripture was through hearing it read aloud in worship.

Fortunately, reading written texts out loud was the usual practice of the day. Ancient texts were meant to be read aloud, whether one was reading publicly or privately. Silent reading was rare, and considered unusual and abnormal. This was true of many ancient civilizations, including the Greek, Roman and Jewish cultures. We see an example of this in Acts 8:30, where Philip overhears the eunuch reading the prophet Isaiah and begins a conversation with him.

One of the reasons all reading was done aloud was that many ancient texts were not divided into separate paragraphs, sentences or even words as they are today. Lines of text might appear like this: THELORDISMYSHEPHERDISHALLNOTWANT.

The most effective way for readers to decipher the text was to sound out the various syllables aloud as they went along. Even the act of writing was done aloud. It was common practice to speak out loud as one composed. This was true whether writing alone or using a secretary.

For these reasons, good writers wrote for the ear, rather than for the eye.

Biblical scholar Harry Gamble has suggested that, “no ancient text is now read as it was intended to be unless it is also heard, that is, read aloud.”

Writing for the ear

The scholars who worked on the King James Version of the Bible understood this. They had a keen concern for how the biblical text would sound as it was read aloud in public worship, choosing their words with care, selecting them not only for their clarity but also for their suggestiveness and richness of meaning.

They worked carefully to produce an exact English replica of the original text, while at the same time infusing it with grace and beauty. Simplicity and clarity were important considerations—the entire translation uses less than 8,000 root-words—but translators were not willing to sacrifice the overall majesty and musicality of the text.

Given a choice between the absolute accuracy of the translation or the elegance and beauty of the language, the translators unfailingly chose elegance and beauty. They avoided the use of contemporary expressions and idioms, deliberately choosing slightly archaic words and phrases like “thee,” “thou,” “saith,” “art,” “verily,” and “it came to pass,” even though these expressions were already beginning to pass out of popular usage by the time of the KJV’s publication.

It was more important to them, Nicholson suggests, “to make the English godly than to make the words of God into the sort of prose that any Englishmen would have written.” The end result was a linguistic style that was slightly different from ordinary speech. They also made very intentional use of punctuation, adding commas and colons to enhance meaning and clarity, and to deliberately slow the pace of public reading.

Their concern for how the book would sound when read aloud was evident when 12 scholars met in 1608 to make final decisions about the text. While one read the verses out loud, the others sat and listened, testing the translation by ear. The reading would continue until an objection was made, at which point there was discussion and debate.

On and on the final editing went, until the entire Bible had been read through. They were, as Nicolson writes, “the new book’s first audience, not its readers but its hearers, participating in, and shaping, the ceremony of the word.”

Hearing versus seeing

Is there a difference between hearing and seeing Scripture? Do we experience Scripture differently when it comes to us in spoken form—through our ears, rather than our eyes?

A study by Carnegie Mellon University in 2001 would suggest that we do. Psychology professor Marcel Just of the Center for Cognitive Brain Imaging discovered that we understand spoken and written language very differently: there are significant changes in brain activity patterns when participants are asked to either read or hear identical sentences.

Why is that? Since sound is temporary, the brain is forced to quickly process and store what it hears in order to absorb what has been said. Written language, on the other hand, provides its own “external memory”; information can simply be re-read as necessary, so the brain doesn’t need to deal with it in the same way. In other words, hearing and reading produce different memories.

Or, as Just puts it, “A newscast heard on the radio is processed differently from the same words read in a newspaper.”

This is something poetry lovers have known for a long time. Poems are meant to be read aloud, and the sound of a poem is as important to its meaning as the printed words on the page. “My work is less to be read than heard,” poet Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote, encouraging readers to “read with your ears.” Robert Frost once suggested that “the ear is the best reader.”

Whether it’s the best reader or not, it’s certainly true that the ear reads differently than the eye. I can attest to this personally. A number of years ago it was my practice to listen to audio recordings of Scripture—usually the gospels—as I took our dog out for her daily walk. Although I’ve read through the gospels many times, it was a rare walk when I didn’t hear something that surprised me, something that sent me straight back to my Bible to check out if what I had heard was really there. I discovered that listening to Scripture is a very different experience from reading it.

Hearing the Bible today

What difference does this make in how we use Scripture in worship today?

We live at a time when print-based communication is giving way to oral and image-based forms of communication: television, radio, the Internet, and video and text messaging. Shane Hipps, a teaching pastor at Mars Hill Bible Church in Grand Rapids, Mich., suggests that this shift is literally changing the way our brains process information—from a reliance on left-brain skills (critical reasoning and abstract thinking) to right brain skills (intuition and emotion).

But along with this shift come some challenges. People today are far less likely to engage complex printed texts like the Bible in the same way they did 50 years ago. Few people read and study Scripture as they once did—something we see clearly in rising rates of biblical illiteracy.

As we move deeper into a culture increasingly dominated by oral and visual forms of communication, perhaps it is time to take another look at the way in which we engage Scripture in worship—how we choose Scripture texts, and how we present those texts to the congregation.

Perhaps even after 400 years, the old King James Version of the Bible still has something to teach us.

Christine Longhurst is a sessional instructor at Canadian Mennonite University, Winnipeg, Man., and regularly leads workshops on worship across Canada. Visit her blog for worship planners and leaders at re-worship.blogspot.com.

Superlatives for the KJV, as it’s known, abound: ‘The greatest work of prose ever written in English,’ ‘The most beautiful book in the world,’ ‘The most important book in English religion and culture,’ one of the ‘books of the millennium.’

Comments

Great article. This is an important point overlooked by many. A few years ago, I sat with my father-in-law, who had a 1589 Geneva Bible, and we compared some of the verses in the Geneva Bible to the KJV in order to assess how different the KJV was from its predecessor. We had heard about the importance of how the new version sounded when read aloud from the pulpit, and the differences were noticeable. I don't believe that the sound of the words had been taken in consideration in the creation of the Geneva Bible, but it was apparent how the KJV gave music to the words.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.