Upon entering the home of Menno and Lydia Wiebe at 10 Concord Avenue in Winnipeg, where they lived for 48 years, one would likely be met not with conventional niceties but with a bright-eyed, depth-probing question, possibly relating to birds and theology, or gardens and ecclesiology, or something else that would never otherwise cross your mind but regularly occupied Menno’s.

Such questions stood as a welcome not only into a truly homey home, but also into the heart of a vivid, ever-unfolding inner journey; into collective creative possibilities; into conversation that never retreated to the banal.

It was as if Menno was just waiting for someone to show up to join him in solving the mysteries of the universe and the challenges of a hurting world. Ensuing deliberations were fuelled by human warmth and hot rosehip tea.

The burst of soulful inquiry at the door prevented one from fully appreciating the hat collection lined up around the cramped back entrance: hats from the dozens of Indigenous communities Menno had visited and endeared himself to. A staggering accomplishment. Prized among them, at least in my eye, was the “Lubicon Lake Nation” hat, a marker of his intimate link to one of the most heart-rending and politically raw Indigenous struggles of his time.

On Jan. 5, after years of declining health, Menno Wiebe died at a care home in Winnipeg at age 88, with Lydia and other family members present.

Most notable among the roles he filled in his life was that of director of Native Concerns for Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Canada from 1974 to 1997.

Perhaps my recollections of visiting him are slightly more interpretive than reality would fully support, but that would not be entirely unfitting. Menno saw uncommon layers of meaning everywhere. On occasion his retelling of an event or conversation I had also witnessed left me genuinely wondering if he was blurring memory and creativity, or whether my ordinary senses had just missed what really happened. His mind worked differently than most.

After completing seminary studies and being ordained, Menno took a Native Ministries position with the Conference of Mennonites in Canada (now Mennonite Church Canada). There, he organized a youth drop-in program that nurtured the lives of numerous young Indigenous people, a surprising number of whom went on to be prominent leaders and lifelong friends of his.

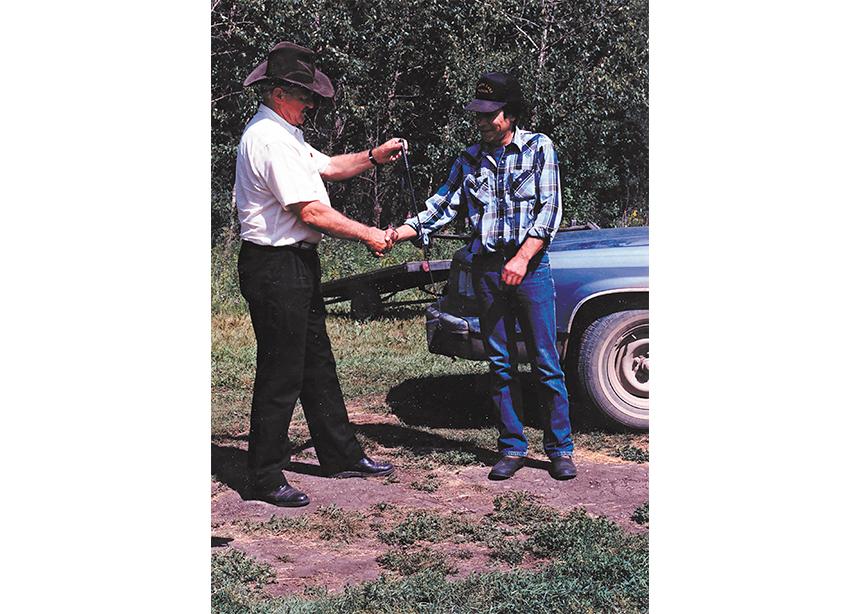

Then he moved on to MCC, where he continued to establish an astonishing breadth and depth of relationships. He knew the leaders who were regularly in the news and the old ladies whose wisdom upheld those leaders. When he showed up, busy chiefs had time to talk and, evidently, present souvenirs. He would find musicians, artists, poets and gardeners, all of whom would receive his nudgings and affirmations. And children would not go unnoticed. He did this from coast to coast, literally: Sheshatshiu, Newfoundland and Labrador, to Port Hardy, B.C.

Not given to the apprehensions and apologetic nature of many well-meaning white people in such settings, Menno would freely hand out advice, ideas, questions, praise and encouragement. In return, he was embraced.

He did things with people more than for them, and was ever observing and learning.

Where he went, people remembered him. They may have mispronounced his name (I heard “Meeno Web” more than once, including in his own impersonations of others) but he was the welcome and enduring face of Mennonites to many Indigenous people.

Over time, he brought many of us into those expanding circles of friendship, eager to pave the way for others to learn from, and walk alongside, Indigenous people.

He pushed boundaries, working in the contentious realm of Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations. He supported blockades, met with senior government officials and helped organize a citizen-convened public inquiry.

He spoke candidly with me about his struggles within MCC, where the organization as a whole often did not feel the pull of Indigenous calls for justice as urgently as he did. But rootedness in the broader Mennonite people was of non-negotiable importance to him. It had to be a “people to people” connection. No “lone rangers.”

Menno lived a multidimensional life. He was a master gardener, joining forces with Lydia at their farmstead on the banks of the Whitemouth River east of Winnipeg. This was a place of potatoes, poems, dreams and hospitality.

He loved art. He sang in the Faith and Life Male Choir, wrote at least two plays, collected paintings by Indigenous artists and, more significantly, he encouraged others. At the Winnipeg youth drop-in, a young Tom Jackson was part of a theatrical production that featured “The Huron Carol.” Decades later, the renowned singer publicly acknowledged Menno’s role.

While doing anthropological studies in Garden Hill, Man., Menno got to know artist Jackson Beardy, arriving home once with a trunk full of paintings by the man who would go on to be part of the “Indian Group of Seven” and a landmark figure in Indigenous art in the ’70s. To acknowledge the importance of Menno’s encouragement, Beardy’s mom gave Menno the cradleboard Beardy began his life in.

Over the years he also taught Native Studies and Anthropology, part-time, at Canadian Mennonite Bible College (a founding college of Canadian Mennonite University) and elsewhere.

Menno was also a pastor. He once invited me to an Indigenous funeral home in Winnipeg’s North End for the funeral of someone I didn’t know. I presumed the intent of the invitation would become apparent. It did not entirely, but I suspect Menno wanted to point to the importance of the sort of behind-the-scenes pastoral accompaniment of which he did so much, often with people whose lives were unhinged and often well outside business hours. The message: Our church must stand with Indigenous people, whether at blockades or funerals.

Menno did not say goodbye at the conclusion of phone calls. He settled on a more open-ended, to-be-continued note, in step with the cultures he so respected. And so now, we who knew him say not “goodbye,” but, perhaps, thanks for the gifts of a life that created so many ripples that continue on.

To see photos and recollections of Menno and to add your own, see canadianmennonite.org/mennowiebe.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.