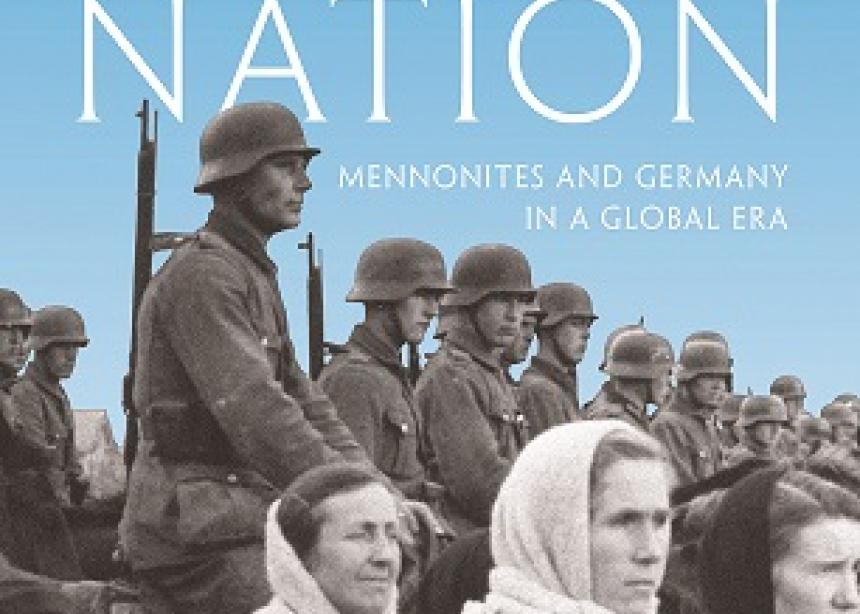

Ben Goossen argues that German-speaking Mennonites of the 20th century had a sense of Mennonite nationality and that this concept of Mennonites as a “chosen nation,” a people with a distinctive heritage, culture and ethnicity, was influenced by the racist ideas of the Nazis. He says he began this study in an effort to understand his grandfather, a retired Mennonite minister from Kansas, who was devoted to the church but who also identified himself as a “proud Prussian.”

The 20th century was a time of global connections with the formation of Mennonite World Conference and international Mennonite publications. Goossen sees this as evidence of a cohesive peoplehood and the concept of one tribe. He also points to the growing interest in preserving a Mennonite heritage, suggesting that genealogical studies, family reunions, historic atlases and church directories prove that Mennonites were interested in preserving their ethnicity and racial purity.

He quotes Peter Dyck of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC), who worked with refugees in the 1940s, as saying, “These Mennonite refugees are neither ‘Russian’ nor ‘German,’” and that Mennonitism is not just a religion but it embraces “all that which culture, language, tradition and a distinct way of life implies.”

Goossen argues that because MCC accepted an ethnic definition of Mennonite when it resettled refugees in Paraguay, ethnicity was profoundly important to Mennonites.

Probably most disturbing is Goossen’s suggestion that Mennonites were Nazi sympathizers. While he acknowledges that the Amish and traditionalist Mennonites had little admiration for Hitler, he points to various individuals who were overtly pro-Nazi. Especially between 1941 and 1943, when the Germans had taken over Mennonite villages in Ukraine, he declares that Mennonites widely benefited from Nazi rule, sometimes receiving goods that had been taken from murdered Jews. He points out that some Mennonites joined Nazi killing squads while others joined the German army, and many became naturalized German citizens.

I appreciated the first part of Goossen’s book as he describes how Mennonites in Germany responded to the rising nationalism of the German states in the 19th century. He gives a vivid picture of how the Prussian Mennonites were more urban and educated than Mennonites from the southern German states. They were also more militaristic and were the first Mennonites in Germany to drop pacifism. Whether or not to join the regular army was considered a personal choice, not a basic principle of the faith.

The latter half of the book was more disturbing. It caused me to consider deeply whether Goossen could be right and my experience of the Mennonite world was just a rose-coloured illusion. Could he be right that if Mennonites “strip away the ethnic trappings of their faith, they are left not with a core of values, but with a process”?

In the end, I found his arguments unconvincing. While he obviously has studied a lot of European Mennonite history, too much of his argument involves the turbulent years between 1941 and 1943. He gives lip service to the profound anti-Soviet feelings of Mennonites in Ukraine but seems overly eager to see their actions as pro-Nazi.

While I have a deep fascination with genealogy and recognize that I come from a distinctive religious culture, those things are not the basis of my faith. In my Mennonite tradition, what binds the tribe together is the foundation of Jesus Christ, not culture or ethnicity, and certainly not race.

I would encourage others, especially historians and theologians, to read this book and carefully consider their own response to Goossen’s argument.

See also:

Historians address Nazi influence on Mennonites

Becoming Aryan

Comments

Those were facts of history that Ben used. You might not like them but unless you can prove him historically wrong, you will have to live with a perhaps an uncomfortable reality.

I am very much in agreement with Keith Johnston's response, that Ben Goosen has been very careful to document his statements with real points of view expressed by actual Mennonites. What is even more convincing is that much of what he presents are the actual words of the Mennonite leadership in the various regions. Whether we like it or not, those were the attitudes and policies that prevailed in the various branches of the Mennonite world. Admittedly there were some, perhaps many, who were uneasy with the official stances taken by the various conferences, etc. But their voices were not really heard. The actual [false] revision of this sad period in Mennonite History took place in the attempt to whitewash and justify the official positions taken in our Mennonite circles!

Thank you, Barb, for an interesting book review. Some years ago Ben Redekop did an interesting study of the North American Mennonite response to national socialism. It was first upheld by well-educated Mennonites who loved to see the renaissance of Germanic culture. Goebbels was published unedited by Mennonite publications, but, as a thoughtful laity engaged with this political ideology, our non-resistant Christology became the theological filter that put a stop to this enchantment, and faithful Mennonites turned away in North America just as the war was about to start. Sound theology became a defense for our communion before the catastrophe of World War II became real.

Ben Goossen's research and writing is blazing a new and important trail for those interested in uncovering German nativist (racist) impulses of many Mennonites both in North America and Europe/Ukraine in the 19th and 20th centuries. Very grateful for his careful scholarship and the light he is shedding on a little examined and not so pleasant aspect of Mennonite history. For those interested in learning more, Bethel College is holding a conference in Spring 2018 entitled "Mennonites and the Holocaust": www.bethelks.edu/academics/convocation-lecture-series/mennonites-and-the...

A couple of points:

(1) What looks like ethnocentric behavior and the development of a 'pure' strain of Aryans in the book must simply be the result of many years of discouraging marriage outside the faith, which is a perfectly sensible custom, as I suspect many marriage counselors would confirm.

(2) Goossen does mention the horrible time that the German Mennonites in the Ukraine had had under the Soviet regime, but only very briefly. Those experiences included: deportation during World War I and destruction of their farms; seeing their entire food supply and harvest confiscated by Stalin's troops in the 1930s; confiscation of their farms after they had rebuilt them; being forced into collective farms to perform slave labor; years and years of famine, when millions of Ukrainians died including Mennonites, and the best they could hope for was a piece of bread; rampant disease, including heart disease from malnutrition; deportation to gulags; executions, and on and on. By the time the German army reached them, in the fall of 1941, it's no wonder the Volga Germans including the Mennonites welcomed them with open arms, nor should it be surprising that boys of military age joined them. All they had seen in their entire lives was the misery inflicted by the Russian Communists, from 1918 to 1941: 23 years. What they did was not moral nor in accordance with their beliefs, but from a human point of view it is not at all surprising. The enemy of my enemy is my friend. Goossen condemns them, perhaps rightly; but what I never saw was any indication that his extensive research had tried to find evidence of people who repented.

Contrary to Draper, I find that Goosen's book is essential reading for North American Mennonites. It brought to the fore the notion of Mennonites believing to be a kind of 'chosen people' which allowed them to take over land and participate in colonization, believing they were more entitled than other races. In addition it addresses racism and Antisemitism that were being spread in the Mennonite community. If we want to undo these things in the Mennonite church, we need to understand where they come from. Through Goosen's work we see how North American Mennonite's "chosenness" lead to violence and colonialism and supporting fascism, as such it provides an indirect critique of the Dutch in South Africa and also critique of Zionism. This is a book we an all learn from!

Lecture presented Nov. 5th, 2019 by the Jewish Federation of Winnipeg: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=al8SWIO2WFM Dr. Friesen and Dr. Werner offer up a well-rounded perspective on the range of Mennonite sentiments toward their Jewish neighbours in the Ukraine. Also, context is given to help understand where Nazi sentiments may have arisen.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.