While Jakob Rempel was being transferred by train from one Gulag camp to another, he jumped from the train in a snowstorm. Ultimately, he ended up in Uzbekistan, near the town of Ak Metchet, made famous in Sofia Samatar’s celebrated 2022 book, The White Mosque. Having escaped the Gulag, Rempel witnessed first-hand the grim end of the unique settlement of Ak Metchet where Mennonites who had left Russia to follow the grand apocalyptic vision of Claas Epp, lived peaceably with surrounding Muslims for many years.

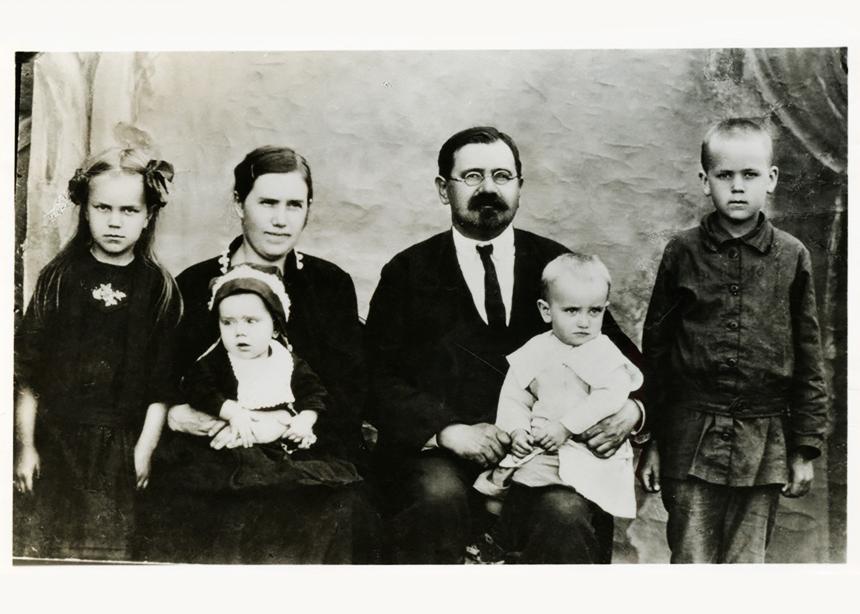

In 2009, Rempel’s granddaughter, Amalie Enns, went on a tour of Uzbekistan, led by Mennonite historian John Sharp. The group visited Ak Metchet. Surrounded by a group of villagers dressed in traditional clothing, Enns shared a version of the following story of the 1935 demise of the Mennonite community at Ak Metchet, as witnessed by her grandfather Jakob Rempel (1883 -1941) and his son Sacha (1915-1985) who had joined him there.

While Jakob and Sascha lived in Khiva—near Ak Metchet—they witnessed the final fate of the Mennonite colony of Ak Metchet, founded by Claas Epp and his followers in the nineteenth century.

The community, according to Sascha, had lived in peace for 55 years, disturbed only once by the local authorities. When the congregation subsequently sent representatives to Moscow to meet with President Kalinin, they returned with a document, written by Kalinin, which ordered the local authorities to respect and maintain the spiritual and material independence of the community, not interfering with them in any way.

They were left in peace until 1935, when the village mayor was ordered by the government in Khiva to call a meeting of all the villagers and inform them that they would be organized into a collective farm. The villagers refused.

The reaction of the government was swift. After several meetings with the villagers in which no compromise could be found, the mayor, the village Aeltester (leading church elder) and all the preachers of the congregation were arrested.

The Soviet authorities came for a third time and the procedure was repeated. The villagers remained intractable; the Soviets refused to give in. This time the newly elected mayor and several farmers were arrested.

For several weeks it seemed as though the Soviets had dropped the matter. Yet the fate of the ten arrested villagers remained undecided. Then came an announcement in the local newspaper: the ten arrested counterrevolutionaries were to be tried in an open trial in Khiva.

Sascha described the incident in later writings:

On the day of the trial Gerhard Wiebe, my father and I took up positions in a certain place in the city where our Ak Metchet friends would pass on their way from prison to the law courts.

Finally they were led past us. What a dreadful sight! Ten pacifist Mennonites, who a few weeks earlier had been strong, healthy men, were emaciated to such a degree that only skin and bones were left. These skeletons dragged themselves like shadows through the streets of Khiva, guarded by a party of the GPU [secret police], armed to the teeth. Two GPU cavalry men rode ahead, two others behind the prisoners, their sabres drawn. In addition, two soldiers walked on their right and two on their left with drawn pistols aimed at the prisoners. Thus surrounded, the whole procession dragged itself to the law court building. Very carefully, taking a roundabout route, we also made our way there.

The proceeding began at three o’clock in the afternoon and continued far into the night. Our brethren defended themselves exceedingly well. Late in the evening, when the accused were given an opportunity for a last word, the men requested a Bible, which their defense counsel had promised to bring. The Bible was handed to them. The first of our men in the prisoner’s dock rose, holding the Bible in his raised right hand. Briefly yet clearly he stated that even the harshest verdict would not shake his faith because this holy book was the foundation of his way of life. Then he passed the Bible to his neighbour in the prisoner’s dock, who basically repeated the first prisoner’s words. The same statement was repeated 10 times.

The sentence for all the accused followed shortly. “Death by firing squad,” was the verdict, repeated 10 times. The assets of all the prisoners were to be confiscated and their families were to be exiled to Siberia.

The very next day several GPU vehicles appeared in Ak Metchet to take away the families sentenced to exile. With lightning speed the news spread throughout the village. The 10 families were herded together in the centre of the village where the vehicles were waiting for them. The loading of the families had barely begun when all the women and children of the village appeared. More than 200 women and several hundred youngsters surrounded the cars. A great din set in. Everything was in turmoil. The children cried and screamed; the adults shouted the demand to release the exiled families.

The GPU refused, whereupon the women of Ak Metchet shouted that all or none should be banished to Siberia. “Either, or!” “All, or none!” was their slogan as they charged the officials. The GPU men defended themselves with their revolver butts, but did not dare to fire into the crowd, a rare occurrence for Soviet officials, who as a rule did not hesitate to use their weapons. In this case, they appeared too cowardly to shoot. The desperate looks and shouts of the women paralyzed them.

“Either-or!” “All or none!”

These calls echoed through the streets of Ak Metchet. The women and children crowded into the cars with the exiles, climbed onto the hoods and cabs of the trucks. Others lay down in front of the wheels with their children, one on top of the other. They formed a wall that defied crossing. Again and again the shouts of the women were heard above the tumultuous noise of the screaming children.

The GPU officials were unable to move. They finally left the scene, leaving behind their vehicles because they could not be moved.

Several days later, all trucks in the district of Khiva were temporarily confiscated by the Soviets. Soon a long column of vehicles approached Ak Metchet. The inhabitants were told to abide by their words of some days ago. “All or none! They had demanded, “All it shall be!” the GPU announced.

Everyone was to take as much luggage as he or she could carry. Bravely, all the inhabitants of Ak Metchet boarded the trucks and cars. Tears alternated with songs as they were transported to an unknown and uncertain future.

A few days later we heard that the Ak Metchet exiles had to wait for a ship at the harbour of Novo-Urgench. Gerhard Wiebe, who shared a room with my father, always had a service horse at his disposal. He rode to the harbour day after day but was not able to speak with the heavily guarded exiles. Only once was he able to make contact with several of our people. Our brothers and sisters had submitted completely to God’s will and remained unshaken in their faith.

Each time Wiebe returned from his ride late at night, my father would jump up from his seat and ask hastily: “How is it going?”

Then one evening, when Wiebe returned at a particularly late hour, his whispered answer to father’s hurried question was: “Everything is over now; they were transported today.”

My father folded his hands and said to us: “Children, this is the greatest heroism our Mennonites have achieved during their history. Let us kneel and pray for them.”

Far into the night we discussed Ak Metchet and the heroism of those women. We almost heard the call, “All or none!” while Wiebe described the scene of the departure. The entire deck of the ship had been filled with the Ak Metchet people waving their handkerchiefs to him while they sang, “God be with us till we meet again.” More and more tears rolled into my father’s gray beard, even though by that time he had probably been hardened to such scenes of grief.

When we finally went to bed, a silvery moon shimmered through delicate clouds, a sign of divine omnipotence.

Adapted from the book Hope is Our Deliverance, by Alexander (Sacha) Rempel and Amalie Enns. Shared with CM by Amalie Enns.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.