In her history of the first 50 years of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Canada, Esther Epp-Tiessen repeatedly defends the decision to create a separate Canadian MCC, distinct from the older organization with its headquarters in Akron, Pa. She presents MCC Canada as the “little engine that could,” struggling for independence, rather than allowing Canadian efforts to be subsumed by the larger MCC, where decisions were made in the United States.

Although she makes a good case that MCC Canada has been a worthwhile and successful enterprise, Epp-Tiessen identifies many of the conflicts between MCC Canada and MCC in Akron in ways that make me suspicious there is another side to some of the stories. She writes from the perspective of Mennonites in western Canada.

On page 84, Epp-Tiessen writes, “The decision to establish MCC Canada’s home in Winnipeg was significant for the larger MCC system in that it ensured a different ‘MCC culture’ than that of Akron or even Kitchener [Ont.]. Surrounded by Mennonites who were of Dutch-German (usually described as ‘Russian’), rather than Swiss-German descent, MCC Canada’s culture would feel discernibly different than MCC’s, though not in easily described ways. The differences would at times contribute to conflict, but mostly they would complement each other.”

This comment is almost the only hint she gives that the creation of MCC Canada was a bit of a political triumph of the “Russian” Mennonites of Western Canada over the “Swiss” Mennonites of Ontario. She recognizes that historian Lucille Marr, in her history of MCC in Ontario, described these Mennonites as being reluctant participants in the creation of MCC Canada, but Epp-Tiessen dismisses this argument, insisting that “the western Canadians made significant concessions to meet the concerns of Ontarians.”

It is interesting that Epp-Tiessen can identify that Kitchener had a different culture than Winnipeg, but she hesitates to describe it. Perhaps she has chosen to minimize this “Russian” Mennonite versus “Swiss” Mennonite controversy because 50 years later it has virtually disappeared. She is correct in her comment that the differences in culture of these two Mennonite groups mostly “complement each other.”

Epp-Tiessen provides good analysis of how the organization has changed in 50 years. She doesn’t get bogged down in too many details, preferring to describe overall trends, now and then zooming in with anecdotes of specific people and situations to illustrate her point. She mentions many individuals, but always within the context of the larger story.

She points out that, although MCC began strictly as a relief organization, it has changed in amazing ways. By the 1960s, MCC was moving into development work. The concept of what it means to be a peace witness changed a good deal in the 1960s and ’70s, and by the 1980s there was new language of “justice.” As MCC Canada grew, it needed to become less “folksy” and more professional. In the 1990s, it deliberately changed its mandate to be less centralized and to give major responsibility for programming within Canada to the provincial bodies.

MCC today has a very complex constituency and the cultural diversity has grown a great deal in the last 50 years. Epp-Tiessen is not surprised that the Manitoba Sommerfelder Church has withdrawn its support from MCC Manitoba, and suggests that it is a bit of a miracle that more groups have not withdrawn. One reason she gives for the widespread grassroots support is that MCC does such a wide range of work that its diverse constituents can always find some project they feel comfortable supporting. She also argues that the hands-on volunteer opportunities have kept people engaged.

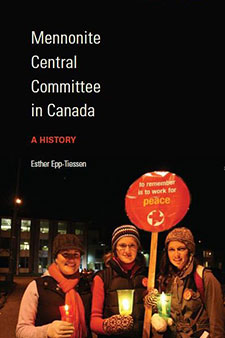

Epp-Tiessen has produced a book about a complex organization that is interesting to read without getting bogged down in details. It’s too bad that the many photos are small, as they would be much more effective if they were in a larger format. The research has been very extensive and the author’s many interviews have given her the opportunity to describe some fascinating behind-the-scenes conversations.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.