Today, when people think of the word “icon,” images of computers and technology come to mind. For centuries, though, the icon—derived from the Greek eikon or ikon—has referred exclusively to images of the divine or sacred. Serving an integral role in the liturgical practices of the Eastern Orthodox Church in particular, icons represent “windows into heaven,” directing the minds and hearts of the faithful towards God.

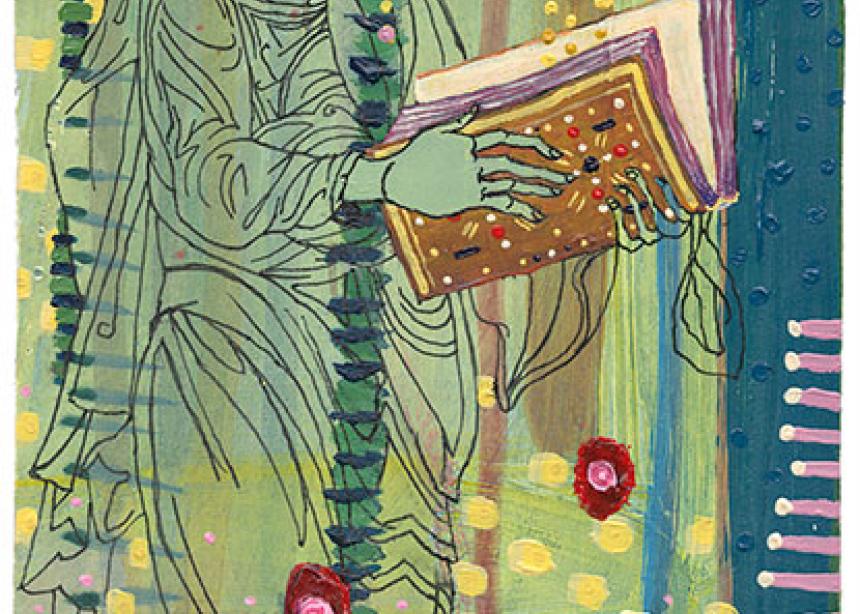

“Embracing the i-kon,” an exhibit showing at the Mennonite Heritage Centre Gallery in Winnipeg until Nov. 9, aims to remind people of the history and impact of icons. Curated by art historian Rachel Baerg, the exhibition features a selection of historic icons, including folk variants from Ethiopia and Asia alongside the work of local Ukrainian iconographer Vera Senchuk and five Winnipeg artists: Michael Boss, Ray Dirks, Seth Woodyard, Christian Worthington and Michele Sarna.

Baerg notes that, historically the Mennonite church has not embraced icons or the visual arts in general, as other tra-ditions have done. She and Dirks, gallery curator, began talking about the exhibit three years ago, with the idea that exploring the tradition of icons might engage the community in discussion on the current relationship between contemporary art and Christian traditions.

“The whole point of this show [is] really to give a fuller understanding of icons, their meaning, their significance, their past and present uses in Orthodox traditions, and [to] see how artists today are tapping into those traditions,” says Baerg, an art educator at the Winnipeg Art Gallery who attends River East Mennonite Brethren Church.

She adds that the majority of people see 3,000 images each day, and, especially for young people, images are a key way of communicating.

“The [Protestant] church is wanting to use that as a way to bring young people in . . . but we don’t know where to turn,” Baerg says. “We haven’t really invested in this rich tradition that sort of ended with the Protestant Reformation. There’s renewed interest and conversation, particularly with Protestants, to look at other traditions—Roman Catholic, Orthodox—with renewed openness [to] renew these traditions of worship.”

The artists included in the exhibit come from divergent faith backgrounds and work in a variety of media, including wood, canvas, clay and metal.

Their works provide for engaging dialogue concerning the appropriation of traditional Christian images and explore the often tenuous relationship between traditional art and the church today, and between contemporary art and the expression of personal faith.

Michael Boss says he first began creating icons in 1996 after becoming disenchanted with the contemporary art world, in which artists typically focus on themselves. He had been investigating his family’s cultural history—his father is Ukrainian Catholic and his mother is Mennonite—and looked to icons as something he could create that did not need to be about his own psyche or his own creativity.

“There’s a long tradition of artists and craftspeople who are working on imagery for churches and personal devotions,” he says. “I picked that up and I just started working on very traditional-type icons as a spiritual devotion and as a way of using the gifts I believe I had been granted, which is this interest in, or orientation toward, being an artist. I was kind of giving [my talent] back to God.”

Boss adds that icons are great tools for meditation because the imagery is of stories from the Bible, or saints and figures from throughout history who have led exemplary lives. “It gets you to focus on the sacrifices they made, the hardships they faced, the glory of God that shone through their lives,” he says. “It gets you to focus on things other than your worldly cares.”

Dirks says that the response to the exhibit has been very strong.

“Certainly for us, the response [is] overwhelmingly positive,” he says. “Maybe in the past these things have been outright rejected, but . . . to present this kind of art, most people are open to it now.”

Baerg hopes people approach the exhibit with an open mind and that they become curious about the role of icons in church history, and how they might be used in Mennonite churches today. “Gradually, if we have an open mind and are willing to learn, I think we will find ourselves with incredible opportunities to experience worship in a whole different way,” she says.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.