"The poor will be with you always.” That is the message that seems to have been so frequently taken away from the gospel when we talk about poverty. That’s not a very encouraging message to someone who has been tasked with coming up with a way to end it.

But it’s true, the poor have seemingly been with us always. And, despite the fact that we have been “fighting” poverty in Canada for decades, the problem seems to just be getting worse, not better. In 1987, the House of Commons voted to end child poverty by the year 2000, yet the number of children living in poverty is larger now than it was even then. So what are we to do?

Albert Einstein said that the definition of insanity is to continue to do the same thing and expect a different result. Perhaps the way to begin is to think about poverty in a very different way. Perhaps the way to think about poverty differently is to not think about poverty at all. Perhaps, instead of thinking about the poor, we need to think about every one of us.

Is it possible that the same things that produce material poverty in some are the things that are producing a mental, physical and spiritual poverty that affects us all? Let me explore this idea and discuss the three pillars that we at the Calgary Poverty Reduction Initiative have come to believe are important to a society without poverty: Abundance, Resilience and Trust.

Abundance

“Look at the birds of the air, for they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns; yet your Heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?” (Matthew 6:26).

I think we’re all familiar with this verse; so familiar, perhaps, that we might not recognize how radical and contradictory it is to most of our current social, economic and political systems. Let me begin by challenging you to consider how utterly contradictory this statement is to some fundamental beliefs that inform our world.

- There’s only so much to go around

Our economy operates on a notion that we probably all understand at some level: Our resources are scarce, yet our wants and needs unlimited. But Matthew turns this entire idea on its head. What we hear Jesus saying is exactly the opposite: Our wants and needs are, in fact, quite limited, and our resources unlimited.

Unlimited resources? Yes, if we truly believe that God provides for creation and everything ultimately comes from God. If we accept this radical notion, it leads us to a couple of other conclusions.

- Retail therapy

Unlimited resources, okay, but “limited wants and needs?” In our consumer culture, “shopping” has become a cultural, almost “moral” good. We hear daily the concerns about “consumer confidence,” and our social and economic health are based on our ability and desire to consume. The market also preaches the doctrine that our consumer choices are always right, as they drive the economy. We engage in “retail therapy” and “recreational shopping.”

Our ability to “find the best price” is elevated to almost heroic status, without regard to how or where our products are produced, or to their impact on our society or environment, while those who can’t consume get left behind. Our need to maintain our status as consumers leaves us working long hours, at the expense of family and community, and keep us hopelessly in debt. But what Jesus says clearly here is that our value as people is not tied in any way to our success as consumers. How then should we value ourselves, and, more importantly, others?

- I did it myself

Lastly, our society prizes independence. The self-made man is held up as the ideal. Self-reliance is touted as a worthy goal, and is reflected in much of our public policies.

But what we hear in this text is that nobody has done it by themselves, as all things ultimately come from God. In the end, we own nothing, being mere stewards of the gifts we have been trusted with, as people deeply reliant on God and each other. And it is in these gifts each of us hold that we find abundance and the confidence to assert that we have, in fact, been provided for and that there is enough for all.

Resilience

But what does this have to do with poverty? If, in fact, we are not independent, but humbly dependent on God and each other, then we exist in community, and it is in community that we discover resilience, a resilience that protects and sustains us. Poverty exists where this resilience is absent.

- What is poverty?

To answer this question, we must reflect on who is poor. Throughout the Bible, the poor are referred to almost synonymously with the widow, the alien, the afflicted and the fatherless. What does it mean to be widowed, alien or fatherless? In biblical societies, it meant to be outside of the structures of society, it meant to be excluded from power and from the structures that sustained people.

If we think about Calgary—where I live—today, we find that things are not that dissimilar. Who makes up the ranks of the poor in Calgary? They include recent immigrants and temporary foreign workers, indigenous people, lone-parent families, people with disabilities or without families. In short, those who are outside of and excluded from our own structures of power and support.

- What are we called to do?

The nature of poverty can also be discerned by what we are called to do about it.

“Thus says the Lord of hosts: Execute true justice, show mercy and compassion everyone to his brother. Do not oppress the widow or the fatherless, the alien or the poor” (Zechariah 7: 9-10).

But what do these things mean? In order to understand this, we need to think about where poverty comes from. In my work with the Calgary Poverty Reduction Initiative, we focus on four sources of vulnerability: personal vulnerability (including our assets, choices and chance); life stages (dependence); disruptive events (disability, economic shock, migration); and systems (economic systems, discrimination, values).

- Mercy

The starting point of mercy is to recognize that we all share these vulnerabilities. We are called to forgive precisely because we are in need of forgiveness, and we are called to show mercy because we all could easily find ourselves in a situation of poverty because we are all vulnerable. Often it is just by chance, or grace, that our decisions have not had life-altering effects.

- Compassion

The starting point of compassion is to recognize that we are all created by God, and God lives within each of us. Hence, Jesus’ admonition, “Inasmuch as you did it to one of the least of these, you did it to me” (Matthew 25:40).

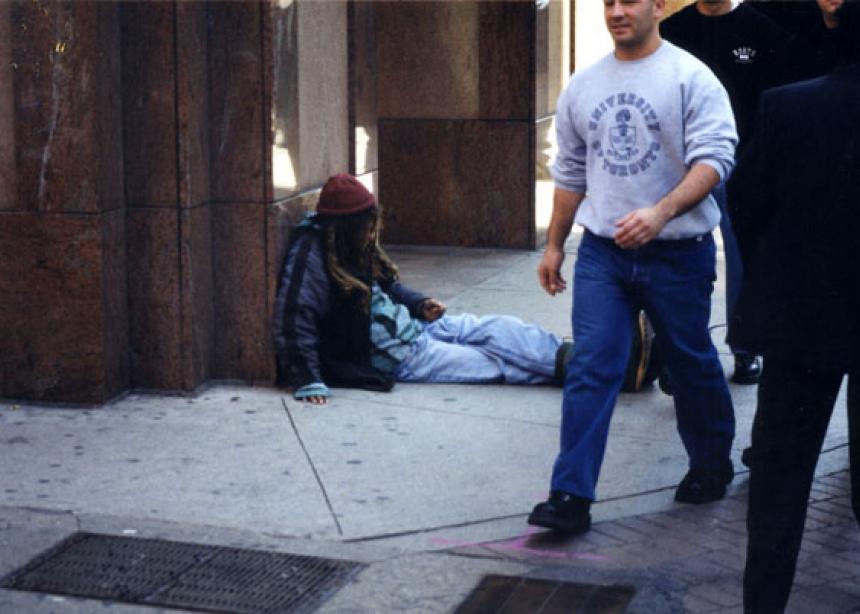

Our society is very good at dividing us into categories. We talk about the poor as though they are a separate species. Once we label people, it is easy to see them as something other than us, and once we do that we can easily assign blame and deny them rights. It is easy to see the question of poverty as a competition between the poor and the non-poor, between us and them.

Even among the poor we have distinguished between the deserving and the undeserving. It might be easy to show charity to a person with a disability who has been rendered unable to work, but how about the addicted?

Charity is important, but the challenge with charity is that it reinforces the power relationships we have with others. It gives me the power to choose who is deserving and undeserving of my charity. However, God makes no such distinctions. We are created equally by God, are equally loved, and are equally in need of his grace. This understanding moves us beyond an us-and-them debate and towards our third admonition: to execute justice.

- Justice

The Oxford Dictionary defines “just” as “constituted by law or by equity, grounded on right, lawful, rightful.” Here are concepts of equity, fairness and also legal structure. In the Old Testament we see such structures embedded in Jewish law, a good example being the practice of Jubilee. How does this apply to the present day?

First, we have international law that provides such structure. Canada is a signatory to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which states that people have a right to adequate income, housing, employment and other basic needs. This is important because, when we talk about rights, we move beyond charity, beyond distinctions, beyond the deserving and the undeserving, and we recognize that we are all equal.

But beyond our obligations under international law, I think we are challenged to think about our own social, economic and political structures and systems. How do our choices as consumers affect the rights of others? What is the impact of our obsession with lower taxes on the most vulnerable? How are we actively including vulnerable people in our workplaces or in our churches? Are we sharing power and decision-making with those who are being affected by our decisions?

Only when we start to answer these questions do we begin to address the challenge of including the excluded: the alien, the widow, the fatherless and afflicted. When we have mercy, compassion and structures of justice, we come to realize a resilience that is present for everyone. This is the foundation of community and it is in community that we experience this resilience.

Trust

This radical inclusion requires one further element: Trust. Communities cannot exist without this fundamental building block. Trust has two aspects:

- Trust in each other

We need to trust each other in so many ways. We must trust each other and our systems to be there to support us when needed. But we need a deeper level of trust as well.

When we share resources, we do so trusting that the people we are sharing them with actually know what is best for them, and we give them the power to act accordingly. And at an even deeper level, when we come to share power and include new voices in our decisions, we place our trust radically in the hands of others.

We ultimately become vulnerable in order to be resilient. Doing so moves us beyond distinctions of us and them, poor and non-poor, and recognizes us all as neighbours, citizens and children of God.

- Trust in God

But we have one final element of trust. And this, as people of faith, is our trust in God, which brings us back to our beginning principle of abundance.

To return to our opening text in Matthew, Jesus admonishes us: “[D]o not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or, ‘What shall we drink?’ ‘What shall we wear?’ For your Heavenly Father knows that you need all these things. But seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness and all these things will be added to you.”

If we believe that all things come from God and that God provides for us, if we show mercy and compassion, if we build a just society with equitable structures that recognize our dignity and rights, and if we place our trust radically in God and each other, does this not begin to resemble the kingdom of God?

In our poverty reduction work, we are building on our faith in: Abundance (that we have been provided for and there is enough for all); Resilience (that we can build a strong community through both our individual actions as well as just and equitable structures and systems); and Trust (that we have the capacity to trust and share power with each other as citizens of equal dignity and worth).

If we focus first on these three things, the rest just may be added unto us. If we build a city where we wisely use the abundance we have been given, where our relationships in community are strong and our systems are just, and if we trust each other enough to include everyone in our lives and decisions, we will have built a city that works for every one of us. And we might just have done something about poverty, too. Almost by accident.

Derek Cook is executive director of the Calgary Poverty Reduction Initiative and a member of Foothills Mennonite Church, Calgary.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.